As a young person, I received on more than one occasion an armchair diagnosis of protagonist syndrome. Sometimes the diagnosis was given in the spirit of good-humored camaraderie – my armchair analyst suffers from the same disease! – and sometimes the mood was less charitable: I’d behaved impulsively, failed to factor in someone else’s viewpoint, etc.

However easy or difficult the diagnosis felt to receive, one thing remains true: they weren’t wrong. I do have protagonist syndrome, a full-blown and severely progressed case, but then so does every single person. There’s something about the human ego that needs a story, and something about being a self among selves in this vast and uncertain world of ours that insists upon agency. The events of our lives must be lined up as evidence of progress, of meaning, and we must be the autonomous decision-makers advancing through these lives in pursuit of that meaning. In other words, there has to be some sense at the center of one’s life, and if the center doesn’t hold, then we’re in for a crisis.

But subscriber, hear me out: there’s a difference between thinking of oneself as a rational, decision-making agent moving meaningfully through her life and thinking of oneself as a Supreme Being among a bunch of unimportant side characters. Yes, there are certainly people who are just antisocial by nature, viewing themselves as superior and others as mere instruments of their will. But I’m not talking about those people right now. I’m talking about how the very normal, human needs for agency and narrative coherence can cause us to behave erratically or even selfishly when we don’t intend to. And I’m going to make a case for why we’re better off satisfying our need for narrative by reading books and watching films instead of fashioning our lives into dramatic stories.

*

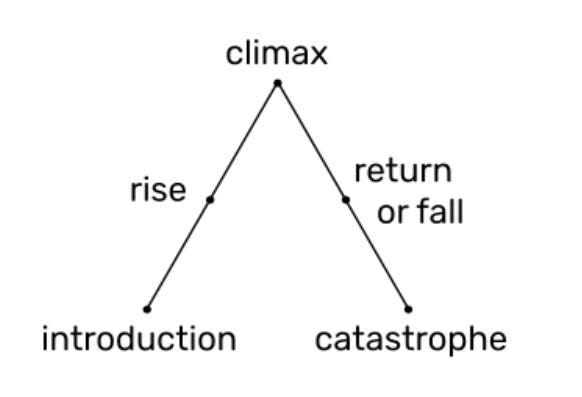

If you’ve taken a high school English class, you’re most likely familiar with narrative structure as represented by Freytag’s Pyramid:

This pyramid is an adaptation of Aristotle’s three-act dramatic structure as conceptualized in his Poetics. It arrives to us via an obscure nineteenth-century German novelist and playwright named Gustav Freytag,[1] and its influence has endured for well over a century. From The Twelfth Night to The Terminator, anyone with a vague interest in mapping human emotion can identify which parts of a story belong to its exposition (establishing the rules of the world), its conflict and rising action (a disturbance or challenge to those rules), its climax (a spike in emotional intensity; dramatic stakes high as they’ll get) and dénouement (establishing the new rules of the world). While we often anticipate a satisfying resolution after our falling action – the hero returns home, families are reunited, the bad guys are vanquished and the good guys prevail – Freytag identified his final act as “catastrophe,” or when the questing hero is met with his “logical destruction.” Though I much prefer my books and shows to have happy endings, I want to stick with Freytag’s original model here. It’s a better fit for my case against life imitating art.

We can see elements of Freytag’s Pyramid in the monomyth, better known as the hero’s journey. Popularized by scholar Joseph Campbell in the mid-twentieth century, the hero’s journey describes a specific version of a dramatic plot in which a hero heeds a call to adventure, journeys to an unknown place and confronts mysterious (often supernatural) forces, and then returns home to share her hard-won insight with her loved ones. From Homer’s Odyssey to The Lord of the Rings to The Emperor’s New Groove, ours is a narrative culture well acquainted with the hero’s journey and its romantic idea of an intrepid individual making sense of an unknown world.

To be clear, I’m not saying that stories with these narrative structures are somehow conditioning those who love them to behave as if they’re the center of the universe, nor am I saying that the structures themselves are somehow wrongheaded or bad. Thinking of yourself as the protagonist of your own life doesn’t make you a narcissist. It doesn’t preclude deep and meaningful relationships with other characters in your life story; it doesn’t mean the constant prioritization of your needs alone, nor willful ignorance of others’ minds and lives. Think back to your favorite stories for the page and screen: how many can you recall in which the protagonist makes no meaningful connections with other people, is in no way shaped by the world around her, seeks to please no one, and never feels trapped by forces beyond her control? If you’re reading only Camus and Sartre, more power to you I guess, but the rest of us will most likely be able to name a whole list of stories whose protagonists weren’t just sympathetic to the needs and wellbeing of others, but deeply involved with such matters.[2]

The issue at hand isn’t being your own life’s protagonist, but the unchecked imposition of narrative onto real life. For you see, subscriber, actual day-to-day living doesn’t move at the propulsive clip of a three-act dramatic play. Not all conflicts can be neatly reduced to good v. evil or us v. them. It’s probably not advisable to force resolutions that aren’t meant to come, nor to assume the dramatic stakes are always as high as they are on a given HBO series. And yet we do these things, often to our detriment, and we do them again and again – not because we’re cursed to some kind of narrative-seeking insanity, but because we can’t help but apply our minds’ narrative-apparatus to make meaning of the world, because we now live in a media landscape that constantly goads us into fear and urgency, and because we’ve drifted farther and farther from the slow and steady consumption of stories that feed our souls.

It used to be that the hero’s journey was something we were entertained and inspired by, a story we could read, hear, view, or drift into Walter Mitty-style before returning to the distinct spheres of our daily lives. Now, gripped by fear and urgency as we are, tuning into another story is too difficult and time-consuming a thing to do. Now, there is nowhere to offshore our plots and dramatic stakes. We’re no longer making sense of our lives via narrative, because we’re living narratives.

What follows are three examples of living narrative, how they could make real life difficult, and how to re-attune to real life.

Narrative Propulsion

If I were to liken your morning ritual to a scene from The Bourne Identity or John Wick, you’d probably laugh in my face – and you’d be right to! Eating breakfast, showering, and getting dressed for work don’t constitute a high-stakes, action-packed sequence one might expect to view through a series of dramatic cuts. To suggest otherwise would be funny and absurd.

So let’s try a different scenario. What if I said, “One day during the pandemic, it just hit me like a bolt of lightning that I needed to live as a man”? Maybe I told you that I was looking at the Instagram of someone who looked very similar to me and had just begun their transition, and that I realized at once both the incredible possibilities self-determination held for me and the years upon years of accumulated pain I’d been harboring from trying to be someone I wasn’t? You might think this was a moving story, maybe even a common one given the amount of transitions that seem to have been sparked by the pandemic, but what you almost certainly wouldn’t think was, “Wow, that kind of lagged in the middle” or “I’m fuzzy on why Raf wants to transition.” And that’s because I didn’t give you access to the unedited footage. I didn’t describe in painful detail the hours upon hours of scrolling on Instagram, Reddit, and Facebook, the many months of reassurance-seeking from friends, the years of internal debate before that. I didn’t give you access to the childhood years, nor the adolescent ones: you didn’t see me being a tomboy and then a young lesbian, you didn’t see the subtle shoulder-checks in my high school hallway, you know nothing of my eating disorder nor the not-so-subtle digs at my nonconformity, and you most certainly didn’t get the backstory on the misogynistic hostility at my workplace. I have given you, for better or worse, the propulsive version of my story – which is to say, the persuasive one – the one which escalates swiftly and nobly to a preordained resolution: things are very bad, and transition is the single solution to all the badness, my life’s merciful deus ex machina. The story began and ended so quickly that you barely got the chance to know me, nor to question that anything but blissed-out euphoria awaits me in the future. Trans or not, we’re all more complicated than that.

Here's another example, one that may feel very familiar to you. Say you come home from work and open social media on your phone. There, you learn of the many Horrors that took place in the world today. Donald Trump deploys National Guard to L.A. says one headline, which someone has re-shared with the caption, “How you know you’re definitely living in a fascist autocracy.” Your inbox pings with an email: it’s senator Bernie Sanders seeking $25 (or $50 if you can spare it, please please please), and he informs you that it’s urgent. A clip on Facebook shows a smart-looking academic being interviewed by an attractive YouTuber. “The situation is dire,” the academic says to the YouTuber. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more dire situation in my lifetime.”

As you stare at these media on your handheld screen – media shown to you by an algorithm designed to show you more and more of what you’ll engage with – you become more afraid. Because you are afraid, you are not inclined to set the screen down and think, “Though I agree with some things I see here, I question the veracity of others – let me take a moment to gather more information from different sources.” Instead, you’re inclined to engage more, to find more clips and reels and headlines that confirm what you already suspect you know. And as you engage your fear intensifies – the whole thing is so inordinately gripping – and when your fear crescendos it will be time for the urgency to kick in. You can’t just stare at your phone, you have to do something to allay the fear! This is the great climax of the story, the call to adventure or decision to take action, whether that action is to numb yourself with several beers or pitch a vase across the room or donate $300 you don’t have to the ACLU. Something must be done, and not for the sake of self-discovery or meaning-making, but because the mounting dread is simply too much to bear.

But what if this played out differently? What if you opened social media, saw a few posts, and then set your phone down and went for a walk in the woods? Say you let your mind wander during this walk, and after a few minutes of fretting about the state of the world, you start thinking about your own microcosm and the people you love within it. You realize it’s been a few weeks since you called your mom. When you return home, you ring her up: she’s seen the news, too, and she’s been thinking about the protests of the Civil Rights Movement and how history seems to move in cycles. Before you know it, you’re watching a documentary about MLK Jr. that she’s recommended and texting her your thoughts before turning in early with a good book.

Hero gets a little worried, takes a walk, calls her mom, learns a few new things, feels better, and goes to sleep early. Is this edge-of-your seat narrative propulsion? Quite the opposite, and I promise there isn’t a writing instructor alive who’d recommend building a story like this. Yet I’m sure any therapist worth their salt would recommend approaching one’s life like this.

A life mindfully lived is slow. It’s not narratively taut. With a few exceptions (secret agents, cult members) the dramatic stakes aren’t sky-high one hundred percent of the time. It’s not especially “good” or “just” to act urgently, contrary to what we’ve been taught, so why not consider the possibility of living slow and reading books about people who live fast instead?

Good Guys v. Bad Guys

If you’re a human reading this, I imagine you’ve experienced some version of the following: you fall in love, the relationship sours, the fighting feels so horrendous you can’t believe this is the same person you fell in love with, you break up.

I spent much of my twenties in this cycle, and every single time it was supremely difficult not to develop a me v. my ex mentality. In such a scenario, I was always the gentle, courageous, noble young woman simply seeking love and connection, and he or she was vile beyond all reason, an emotional terrorist. The more I mythologized the situation, describing the tortured relationship to friends or family, the less and less human the ex became – more sadistic Disney villain than anxious and confused person behaving chaotically. And of course, there was little room for my own chaotic and confused humanity: I had to be hero – not antihero, mind you – and victim rolled into one.

And before your cortisol levels start spiking, subscriber, let me be clear: my intent here is not to justify mistreatment or abuse of any sort. It’s merely to suggest that there’s freedom to be found in loosening our collective grip on life-as-narrative. Whether what transpired in a given breakup was run-of-the-mill bickering or something far more concerning, we’re liberating ourselves from the sweeping logic of the three-act drama by saying, “This isn’t a dynamic I want,” adjusting it or extricating ourselves from it (to the best of our ability), and then trying to figure out how such patterns might be avoided in the future.

Hero has a fight with her partner, asks for some space, does some introspecting, returns to talk it over with him, and the two decide to part ways on good if bittersweet terms. Again, it’s no journey to Mordor, but perhaps that’s because it doesn’t need to be! Take it from Aristotle: there’s far more emotional catharsis to be found in reading a novel than enacting one.

Let’s return to the doomscrolling example from the previous section. After consuming numerous posts, videos, and memes about the direness of our sociopolitical situation, it might feel like second nature to assume an us v. them mentality. You are on the right side of history, and anyone who doesn’t believe what you do is on the wrong side of it. This could extend from political opponents real and imagined all the way down to the parent or grandparent who’s still fumbling your pronouns. It might seem as if every single person on this continuum is an enemy to freedom and justice and goodness and ought to be stricken from your purview – from your life, even.

Now, I hope you’ll hear me out again: I’m not demanding that, say, the racially minoritized go out right now and break bread with card-carrying neo-Nazis (though such things have been done, a fact I find incredibly inspiring). What I’m suggesting instead is that we treat the real world as the real world and not as if it’s an unknown land host to supernatural forces of evil. What we are is a group of ginned-up humans in ideological gridlock – disparities in belief may seem worthy of contempt when mediated by a screen, but that contempt is somewhat more difficult to maintain face-to-face. I wrote last year about how some of the closest friends I made in rural America – people who showed immense love and understanding to me when my life felt like it was imploding – were people whose voting records differed from my own. Perhaps this sounds impossible, but if we consider that real life is textured differently than a three-act drama, punctuated with opportunities to slow down and introspect and have conversations, then this might make a little more sense.

To the many smart and ambitious young people reading this (you know who you are): You are not Goku, and the family members who keep fumbling your pronouns or struggling with your politics are not Frieza and/or Vegeta. Contrary to the thousands of posts and videos being pushed in your face, having conversations with people who genuinely want to talk to and learn from you isn’t “excessive emotional labor” or “dangerous,” and estrangement isn’t the catch-all answer to the frustration you’re experiencing right now. Without consulting the internet, use your better judgment and ask yourself whether there is a clear and present danger in maintaining a relationship.[3] If your gut tells you there isn’t, then consider having a conversation, writing a letter, or sharing a piece of your art with the family member. I promise that, 99.99 percent of the time, no one is making an attempt on your life with pronoun (mis)usage.

Resolution/Catastrophe

A decade ago, I had what might be clinically described as Very Bad Mental Health. I realized many years later that my anxious/depressive/antic condition was stoked by my obsession with forcing outcomes.

I had, like any sensitive young person desirous of doing the right thing, an obsession with goodness and justice. I had read many books and watched many movies and episodes of TV, so I was well attuned to what a narratively satisfying resolution to a problem ought to look like. If I and members of my social and/or political cohorts were the good guys, then our problems ought to end with the vanquishing of the bad guys. Our antagonists had to be somehow neutralized so they couldn’t harm others as they’d harmed us.

Perhaps this begins – as it did with me in my early twenties – by reporting an ex-boyfriend to OK Cupid so his profile could be banned. He’d lied to me, stolen $1k from me, and been a scrub: I felt that no woman should ever have to endure his heinous abuses again.[4] But such things escalate, as they always must in any dramatic narrative: I found I could not rest until the awful boss was forced to stop tormenting me, the horrific disorder of the country was reformed to a state of peace and equitability, the broader world that owed myself and my friends spotless understanding and compassion was somehow made to give it to us. I was, in other words, on a bitter and resentful warpath, alternately trying to bring about justice and then despairing at my incapability of doing so. It began to seem as if things were quite simply shit, and always would be.

What tended to follow for me was not a peaceful resolution, but a Freytagian catastrophe. If things were bad and could not be made good, then perhaps the universe was a fundamentally unjust place and nothing mattered at all. Perhaps I ought to throw in the towel and get really high and drive my car really fast and send a string of impulsive and annoying emails to professional contacts. In such a nihilistic state, self-destruction seems like the only sensical option.

Does this mean, subscriber, that one ought to uncritically swallow the Kool-Aid of inequality, accept maltreatment, or otherwise abandon pursuit of the good? Of course not (perhaps you’re sensing a pattern by now): it merely means that when we set our sights on a specific outcome and define that as the only possible good outcome, we delimit our chances for growth and self-knowledge by once again denying real life its texture. Instead, we circumscribe ourselves to the blunt logic of a Marvel movie – villains must be vanquished, superheroes must cheerfully eat shawarma afterwards – and foreclose on resolutions that may surprise us.

What if, instead of the awful boss being “neutralized,” we simply leave the job, learn to trust our judgment, and discover new career opportunities we didn’t even know existed? What if, in the midst of what feels like widespread political confusion and tribalism, we can discover pockets of love, connection, and equity that don’t necessitate a top-down restructuring of the American polity? What if we can supply ourselves with the compassion and understanding we’re demanding from the historically unreliable world – and what if learning this skill is somehow more satisfying than trying to extract goodwill from others?[5] What if the resolution isn’t cinematic, but it feels better?

*

This, subscriber, is my hard-won scrap of insight: the narratives that satisfy us on the page, stage and screen are not the same ones that satisfy us in real life. Which is also to say that we consume these narratives not just for enjoyment, but in order that we might not live them. Reading a book is a healthy way to satisfy the human need for narrative coherence, for grandiosity and derring-do, for heroism and justice and mystery and rationalizing the unknown. But real life looks different from the Iliad or The Goonies. And it can feel different — i.e. better — too.

There’s nothing wrong with being the protagonist of one’s life – I’d argue that such a thing is less a syndrome than an inevitability – but you must be ready for an unconventional type of story, one with far more than three acts, no bright line delineating “good” from “bad,” and some very surprising resolutions. Such a life story may not get optioned for a film adaptation, but then I’d argue that’s for the better. After all, there’s no dramatizing a life well lived.

[1] So obscure that few remember his alarming political views: Freytag’s Soll und Haben (Debit and Credit, 1855) was a work of bald-faced racism and antisemitism no doubt beloved by many members of the Third Reich.

[2] Romeo and Juliet, or: Toxic Empathy in Verona

[3] Physical, emotional, or financial abuse? Demonstrable malicious intent?

[4] Irony of ironies: years later, an ex-girlfriend would report me to Tinder. My crimes included leaving town to take an academic job in a different state, being outspokenly anxious and depressive, not affirming her anarcho-capitalism.

[5] To be clear, self-compassion is a skill I’m still very much working on as well!