One of the many unpleasant outcomes of coercive control is losing a lot – including, even temporarily, a coherent sense of self, material stability, etc. – and one of the many unpleasant outcomes of losing a lot is instability. Even after you’ve begun rebuilding your life and have managed to relegate major insolvency to the rearview mirror, the rupture in your past is still sending shockwaves through your present, and will for much longer than you’d like. Maybe you’re walking your dog down the street and then you’re suddenly frozen with the memory of your guru-antagonist. Or maybe you’re shocked to realize that being a lifelong member of the middle class somehow doesn’t preclude falling so far so fast that $25 becomes an impossibly large amount of money. The rhythms of your daily life are interrupted again and again, if not by dreams or fears or memories, then by upheaval. You need to get away from your captivity: you need to change your job, you need to sell your car, you need to leave the house you’re living in.

I won’t waste too much breath recounting my cult-of-one experience (new subscribers can learn more here or here if you’re curious). Right now, I’m more concerned with the shockwaves.

We’re moving again, the fourth time since last June. It’s another move of necessity, though not emergency: unlike the previous three moves, we’re not escaping anything, and we’re far from a total nadir in terms of energy and finances. Still, it’s moving. Still, I feel ripped up by it. I have to miss a family reunion. I have to put some creative projects on hold. I’m tired of my life being interrupted. I want to write and watch documentaries and eat ice cream with my wife and catch my goddamn breath instead of lugging boxes up flights of stairs yet again. For a couple weeks, I felt hurt by the state of affairs and wanted to externalize that hurt: I snapped at my wife, I was anxious and brusque with friends and collaborators, I became exhausted and over-emotional and made it everyone else’s business (so: I became solipsistic). I felt embarrassed, blamed myself, feared a crack-up, worried I was once again becoming someone I didn’t want to be.

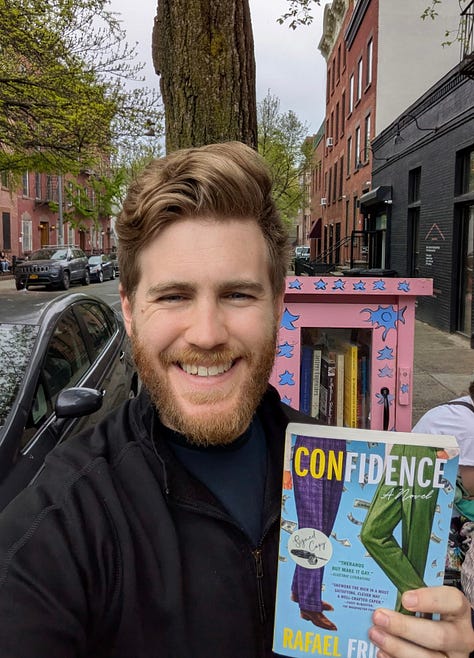

Yesterday afternoon, I did something to calm myself down that I’ve been doing a lot recently. I threw a bunch of old books in a satchel and stocked some little free libraries. The books included a 90s paperback of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, a book about androgyny and Jungian psychology, and A Course In Miracles (we have two copies). The books I found included What to Expect When You’re Expecting (1984 edition), Philip Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect, the aughts YA classic Feed (I’ve always regretted never checking it out in high school), and Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility. I grabbed The Lucifer Effect and Feed – they pair well together – and came home feeling if not completely settled, at least more grounded. Each little free library had been an eclectic reflection of the goings-on of the block, a cheery way for neighbors to learn what’s on each other’s minds and exchange some ideas. Nerd that I am, I’m genuinely cheered by the possibility of ideas being exchanged uncritically.

This morning, I woke up thinking I want my life to be like how it was before. I was ready to tuck into the pity party of this statement, maybe even lose myself in some waves of self-righteous indignation, but then another thought occurred: But how was it before? Before, I hadn’t met my wife. I judged myself by numbers: pounds on the scale, copies of books sold (always too much or too little). I was if anything more prone to righteous indignation and reactivity, but the veneer of material stability cloaked it. Sure, I wasn’t moving house every three months, but I was moving from panic attack to panic attack in my mind. What was there to be gleaned from material stability if I was operating with such a low sense of self-worth? Beyond being clothed, fed, and sheltered (which I am now, and never ceased to be), there was little on offer besides sameness. And “maintaining sameness” isn’t exactly a guiding value I want for my life.

One thing I love about little free libraries is their variety. I’ve come across many, and each has an unmistakable personality. Some are dressed up like little houses complete with mosaic-tiled roofs, some are shaped like Airstream trailers, some are affixed with wooden fish, some are tall, some are short, some are bedraggled and missing their doors, some are immaculately maintained with jars of laminated bookmarks, some are double-wide with little faux-garrets on top, some are painted vibrantly with pictures of fairies and hummingbirds and vines, some are registered while others are not. They stand in front of private residences and businesses and full-sized libraries, churches, synagogues and gyms; they pop up in hospitals and waiting rooms, in community centers and historical societies and coffee shops. Sometimes those who tend them have specific intentions for them – I’ve seen adult and youth little libraries built close together, one shorter than the other, hand-painted signs designated which is which – but more often the only intention is that this wooden box will house books that passerby may take or leave at will. And so the little free library becomes a kind of bellwether for the community: we know what people on the block are thinking and reading about by the books within. We know when the library suddenly fills to the brim that someone has done a shelf purge. We know that it’s school season when certain little libraries are overtaken by middle-grade novels and picture books and that school’s out when they fill once again with Janet Evanovich and Robert Ludlum. We can delight in the collision of titles in little free libraries, the sheer randomness that would strike any catalog-minded librarian as Dada levels of obtuse. Sure, here’s Mindy McGinnis’s The Female of the Species next to Son of Hamas next to 50 Delicious Crock Pot Recipes. Why not?

One thing this most recent move has forced me to reckon with is my attachment to place. This is such a human thing, such a having a home thing, and yet I hadn’t really allowed myself to acknowledge it as a reality for me, and thus a potential site of pain. Even though we’d been eager to escape a dangerous situation, it was hard to move away from the community we’d built where we lived before, and it’ll be hard to move away from this place, too. Part of adapting to a place is coming to love it, from the broad brushstrokes of its character (the weather, the nature, the architecture), to the specifics of your little slice of it. I’ll miss the big, knotty tree I can see out my window as I type this, and the delicious coffee shop down the block, and of course the little free libraries: the one that’s always overfull, the periwinkle one with the periwinkle bench, the one that has an adjoining plastic bin for games and puzzles. Growing to love and then leaving these things is not a rupture as big as having your mind claimed by an accessory to a cult leader, but it’s a rupture nonetheless. Perhaps getting to grieve the smaller losses is a sign of progress. Honestly, I’d rather not grieve at all, but such stipulations are impossible in life.

When my wife got tired of lugging her old yearbooks around among residences, she suggested with a twinkle in her eye that we stash them in little free libraries. When I looked surprised, she said, “Isn’t a little free library basically a community art project?” And she’s right. A little free library isn’t just a bellwether of taste and ideas or a place to access books without needing to flash a credit card or proof of address: it’s both those things and a cheerful nonsense-redoubt where art is the object and commerce doesn’t exist. Remove “buying” and “selling” from the picture, and who’s to say what people are in the mood for? If I can be chuffed by a well-aged paperback of The Phantom Tollbooth or a 1965 edition of the local VFW’s hair-raising collection of casserole recipes, surely someone will delight in finding my wife’s 2005 high school yearbook from small town Oklahoma.

With this in mind, I started stocking little free libraries with copies of my own books. It became a hobby from which I derived great joy, making meaningful-to-me deliberations about which book should go where and when, thrilling when they were taken or transferring them to different little libraries when they weren’t. I loved contributing to the community art project, wherever I was. I felt like I was leaving pieces of myself in different places without actually losing anything. In fact, I was gaining something: the feeling of having-given, the feeling of being part of a place, even if in just a small way, even if that place was changing and I was too.

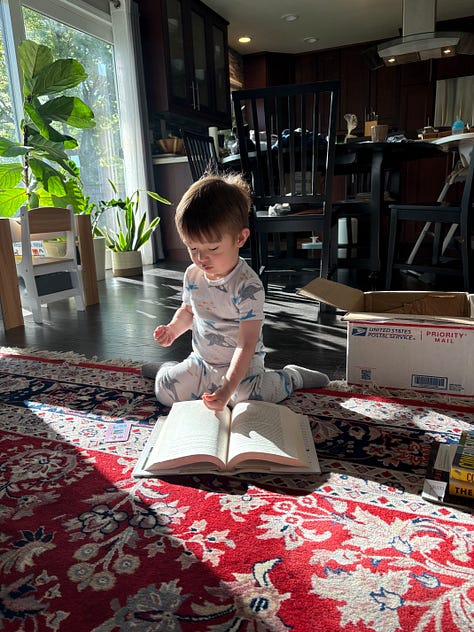

This past winter, I got to give a reading at the indie bookstore in the town where I went to college. As often happens at readings, the store ordered more stock than they sold, so I hatched an idea: I asked my far-flung college friends if they might consider ordering a signed copy of Confidence from Content and then stocking it in a local little free library. Some of them so liked the idea that they were willing to stock other books – a friend in California kindly fielded an entire box from me! I asked them to send selfies of the book-stocking, not just because they’re sweet and photogenic people whose snapshots I imagined including in an essay, but because I wanted to witness from afar a version of the magic I’d been experiencing up close: something I’d made gifted to a complete stranger by a friend, parts of my life scattered across the country, stories that could be chosen or not, read and then kept or gifted or put back. I loved participating in other communities’ art projects from afar, loved my friends’ updates when the books were taken, imagined each book’s transit from box to shelf to library to resale store. Perhaps some of them even found permanent homes. Perhaps some of them never would. It feels freeing not to be troubled either way.

In a period of my life that has felt so endlessly determined by the shockwaves of another’s criminal intent, where the temptation to circle the drain of permanent victimhood rears itself far more often than I’d like, stocking little free libraries has felt like a freedom. Better, even: it’s felt like a lot of little freedoms, given the uniqueness of each library and each book’s path, no book’s fate bound and determined by anything more than the interest of a future reader, their proximity to a little library, the direction the breeze happens to be blowing on a given day.

If you’d like to join me in my little library stocking project, order Confidence from Content Bookstore or Bookshop.org and stock it in a local little free library! If you send a selfie or receipt to frumkinr[at]gmail.com and include a preferred mailing address, I’ll send you a gift!

Beautifully written! Love this: "Perhaps some of them even found permanent homes. Perhaps some of them never would. It feels freeing not to be troubled either way."

"Dada levels of obtuse" and "community art project" are indeed such accurate ways to describe the experience of a Little Free Library. The contents of Little Free Libraries in south Minneapolis have given me so much joy in their variety, as you wonderfully describe! Also, friend, if your move has not already happened and is in the Twin Cities, I am happy to lend effort toward getting your fam and possessions from point A to point B.