Contrary to what this title may seem to be implying, this is not a multi-part essay about a single acid trip, nor is it a paean to hallucinogens. (They can be extremely helpful, yes, but they are a single piece of what I’ve found to be one of those thousand-piece tabletop jigsaw puzzles, the kind with a highly detailed scene of, say, the cosmos, or a dense Hungarian forest, or a busy train yard with tracks and train cars going every which way – the kind whose edge pieces always seem to get lost under the rug or somehow wedged between the leaves of the table, and which are always showing up at the oddest times, exactly when you need them least.) What I intend to focus on here is how a single day of altered consciousness a) supplied a broader context for many other “downloads” of information I’d stumbled upon at various moments in my life, information suddenly received (or perceived?) during periods of similarly altered consciousness or just during conversations with friends or while looking at a particularly magnificent tree; b) helped me understand how these various “downloads” could be applied to the practices of writing and teaching writing; and c) what implementing this new pedagogy has looked like. (Spoiler: it’s been so fun!)

In this, the first part of this two-part essay, I’ll be focusing on how this particular trip occasioned some deep realizations for me, and how I came to understand that those realizations could actually be applied to the “professional” (love to use this term loosely) creative life I live outside my skull in addition to the decidedly “unprofessional” (i.e. in no way inspected, judged, or surveilled) spiritual life I live inside it.

A little background. I, like most writers and teachers of fiction in the contemporary Anglo-American tradition, was instructed to take a formalist approach to the crafting of my stories and novels. What this means is that I was encouraged to focus more on the mechanics of fiction – craft elements like scene and dialogue and syntax and exposition and characterization – and less on what fiction concerned itself with. For a long time, this made perfect sense to me. For a story or novel to “work,” it needed to have a coherent aesthetic sensibility, needed to “pop” on the page in a way that screamed: Yes, I understand the nitty-gritty of crafting an appealing art object in the prose medium. I, too, speak the language you were trained to speak. Plus, whenever my peers in various workshops took issue with a story’s content, the criticism always felt hollow and ad hominem. If you didn’t like the contents of a story that was about, say, a newly divorced woman going on a road trip, that seemed to say more about you as a disdainer of stories about women and less about any kind of mistakes the writer was making.

Now, onto the trip. We planned the trip in our backyard as a celebration of our friend Anais’s twenty-eighth birthday this past June. Anais and her partner Juarez are fellow Chicago transplants to the biodiverse ecosystem of Southern Illinois (henceforth referred to as SoIL in this Substack), owners of a very delicious restaurant here in Carbondale, and purveyors of a combined chill, openness, and sweetness so powerful one might describe it as medical grade. An hour or so in and we were lying in the grass watching the individual currents of vapor that make up clouds scintillate and coalesce and disintegrate and coalesce again, as if from nothing, and I was feeling a kind of peace I hadn’t felt in some time – quite possibly not since early childhood, when I was very confident that I was very cool, and that the world was a fun and silly and exciting place, and that the best thing you could spend your day doing was learning. I then proceeded to apprehend a rather soothing set of thoughts, which I captured thusly for inclusion in the “about this class” section of my grad class’s syllabus (without mention of the acid, of course):

Put simply, I had a spiritual experience. I didn’t see a god or gods or have a religious epiphany that’s rendered me a devout follower of a certain group. I was simply lying in my backyard with my partner and two of our friends and I was struck with a sense of awe and wonder at our little patch of grass and sky, as well as the distinct feeling that the “self” I had so relied on in the past – to become a successful writer and teacher, to become well-liked and semi-known among literary circles – was in fact not a “self” at all, but a collection of molecules whose rightful place was in nature. I realized that I am nature, that we all are, and that the only thing drawing distinctions among our spirits (which exist independent of our animal flesh) was the human ego and its obsession with certitude, safety-in-conformity, and prestige. I was familiar with the Buddhist concept that all earthly desire leads to suffering, but never before had it resonated so clearly with me: I was suffering because I desired to achieve a certain status and celebrity with my writing that, once achieved, would only leave me wanting more status and celebrity. It was a useless carousel of desire and it was leading me nowhere.

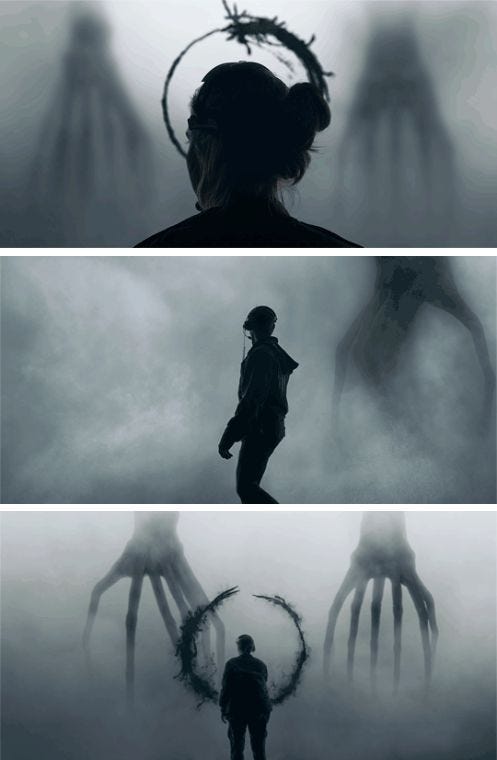

Unlike other hallucinogenic trips I’ve taken, this one wasn’t all high-energy, scenery-melting pyrotechnics. The doors of perception hadn’t really been thrown open so much as nudged, and I found myself sidestepping into a relationship with reality that is probably best described as “askew.” I felt as if I was somehow orthogonal to the human world, like I was emerging from it into a different plane, and I could see how remarkably different the place where my feet were was from the place where my head was. My feet were on the dusty terra firma of ranking, competition, and judgment: the soul as finite, the novel as demonstration of artistic prowess, work as the ultimate arbiter of meaning, the ego as dominant interior monologuist. But my head seemed to have merged with those currents of vapor the four of us had become so fascinated by, and I was catching a glimpse of this pleasant alternative reality: immaterial and insubstantial and ever-shifting, diaphanous, dizzyingly colorful, otherworldly. In this place – wherever I was – the things that I’d been told mattered, that I’d driven myself to places of intense (at times even dangerous) suffering over, actually didn’t matter at all.

A brief flashback to 2015. It was in this year that my friend Viv and I took a very potent research chemical and I experienced ego death. I was twenty-five, she was twenty-three: she had already begun transitioning and I wouldn’t so much as question my gender for another six years (yes, I’m a COVID tran). She had gotten this fake acid – called 25i, and first manufactured in 2003 “for research purposes,” according to a Wikipedia article that seems to be suggesting I was lucky to get out of this experience alive – and we did it together in a forest preserve adjacent to a hyper-conformist Midwestern town. It was during this rather intense experience (which saw Viv empty the entire contents of her stomach into some shrubbery, me hallucinate a two-moon/Tatooine-like planetary situation, and the two of us have very different but equally enthralling experiences in a McDonald’s bathroom) that I absolutely lost my sense of self, felt my nattering panicking ego shrink and give way to what I’ve come to call “a purely sensing being-in.” I’d become a glowing orb whose only function was perception, who could float through the air and underwater and into minds, unfettered by a meat suit and its irksome fears and preoccupations. It was an incredible feeling, kind of like being dead and at the same time feeling good, somehow part of something bigger than myself, and I remember wandering around a playground at dusk in the manner of many a stoned twentysomething, watching Viv furiously pump her legs on a swing to achieve heights that struck me as superhuman, thinking with a calm assurance: Death is not the end.

I had no idea what to make of this experience for years until this recent trip on Anais’s twenty-eighth birthday, when it occurred to me that the statements Death is not the end and I am nature actually have a lot to do with each other. Namely, that we are all always extending beyond our bodies in senses both molecular and epistemic: i.e. We are made of the same carbon/stardust/atomic “meat” of which everything else in this universe is made, and we are capable of expanding our consciousness beyond our skulls, into realms of which we were previously unaware, and in which the epochs-long stories baked into the various other clusters of carbon/stardust/atomic “meat” — their countless twists and turns and transmutations from rock to tree to cloud to dog to bird to human — become so stunningly, overwhelmingly apparent that we are left with no other option but to pray or cry or maybe celebrate. I certainly felt like celebrating, lying in our backyard and looking up at the clouds. The idea of the eternity and interconnectedness of all things stilled a panic in me that had been raging for nearly two decades.

And then writing changed for me. I realized that I was no longer satisfied by the creative act as an approximation of perfection. My idea of beauty shifted. I became less interested in the story, novel, and essay as demonstrations of individual technical skill and more interested in them as messy vehicles for describing the ineffable. The novel is a capacious, many-corridored form, which makes it perfect for exploring the cosmic in the mundane and the mundane in the cosmic: what better place than a novel to attempt an understanding of the world, to examine and interrogate your and your characters’ beliefs, to try out omniscience by jumping into multiple, diverse points of view? And of course the novel isn’t the only discursive, pluripotent prose form. The philosopher Max Bense (1910-1990) described the essay as a Versuch (which means “try” or “attempt” in German), and I love that idea. That what we’re doing when we write isn’t about succeeding so much as trying, that we are always trying – in prose as in any art, nothing is ever finished, nothing is ever perfect, no argument made conclusively, no axioms revealed (don’t tell this to analytic philosophers – they’ll become much sadder than they already are). To see my writing as ever-emerging and ever-becoming allowed me to begin to see my students’ writing the same way, and I knew that I wanted to teach creative writing classes that educated students in more than just the same old dicta of craft we’ve all been told for ages.

It began to feel important to me that my fiction students engage with philosophy. It felt important that they know they could ask big questions and then attempt imperfect and inconclusive answers through their art. The pitfalls of the rigidly formalist contemporary novel and the didactic 19th century novel of ideas are of a similar breed: mainly, they both seem too obsessed with perfection, with being “right,” with the “genius” of the individual creator (a concept that didn’t do the German Romantics too many favors and certainly isn’t doing contemporary writers many, either). I realized that I wanted to teach students to write a different type of novel (and story, and essay) – one that comes to all the lapidary, deeply humane qualities of truly gorgeous prose not by way of technical precision nor obsessive polishing, nor by way of “rigor” nor “logic” nor “certitude,” but by way of meandering, of a considered exploration of one’s themes, of contemplation and pleasant surprises. And yes, I would incorporate conversations about content into my workshops, but instead of dismissing stories out of hand because of what they’re “about,” our critiques would be suggestions of how the writer could explore their thought more deeply, could expand their mind by imagining the interiority of this or that character, could better understand their creativity as a form of intersubjectivity, a testament not to solitary achievement but to our delightful, creaturely interdependence. I found myself returning to The Jungle and Gattaca as examples of stories that sparked large-scale conversations about human rights and social welfare. I revisited some of my favorite books and stories by Octavia Butler, Ted Chiang, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Han Kang. Slowly but surely, the syllabi for my fall 2023 classes began to come together.

Coming soon: part two of this essay, in which I talk about how these unusual creative writing classes started, how they’re going, and the wacky in-class activities we’ve been getting up to! Stay tuned ;)