My dear, patient paid subscribers: welcome to the first in a long series of rewards for your generous support of my work! I am so thrilled to be sharing my first paywalled piece with you.

This one falls in the “unpublished short story” category. During COVID, a good friend and I were perturbed by the fact that, even though everyone wanted to write books and stories about viruses, nobody seemed to want to publish those books and stories. So my friend and I dared each other to write the best possible plague story we could. We were inspired by, among other things, the Villa Diodati dare that resulted in Frankenstein and the frame narrative of The Decameron (a bunch of people hiding out from a plague and telling each other stories). We also really, really wanted to be the exceptions to publishing’s unspoken “no COVID fiction” rule. Ah, youth!

And although I didn’t exactly have the luck of an eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley with the story I wrote on a dare, I didn’t really care, because I loved what I came up with, and am still in love with it two years later. This story is my attempt to talk about addiction through the eyes of a hapless ex-professor who’s running drugs for a former student as a deadly virus is claiming lives and history appears to be grinding to a halt. (Stay tuned — I’m planning to turn this one into a novel. It’s how Confidence began, after all!)

I hope you enjoy “The Ministry of Comfort,” and the accompanying original illustrations by queer zoomer art phenom Jamie Mica Dewitt!

Much love,

Raf

The Ministry of Comfort

Sangamon was dead and blind. Blind because it had always been blind, ending in the back of a brick apartment building that had been abandoned for ten years, the bricks soft and texture-less like bar soap. Dead because no one was in it, and there were always people in it, kids bouncing basketballs and baseballs off the three buildings surrounding them, drawing chalk circles on the pavement, the more athletic of them running up and doing flips off the brick. People politely called Sangamon Sangamon instead of an alley, because to call Sangamon an alley would be an admission that there was something as coarse and dangerous as an alley in our community. What happened in alleys? Gangsters were cornered and shot by cops. Women were held at knifepoint and raped. Junkies shot heroin.

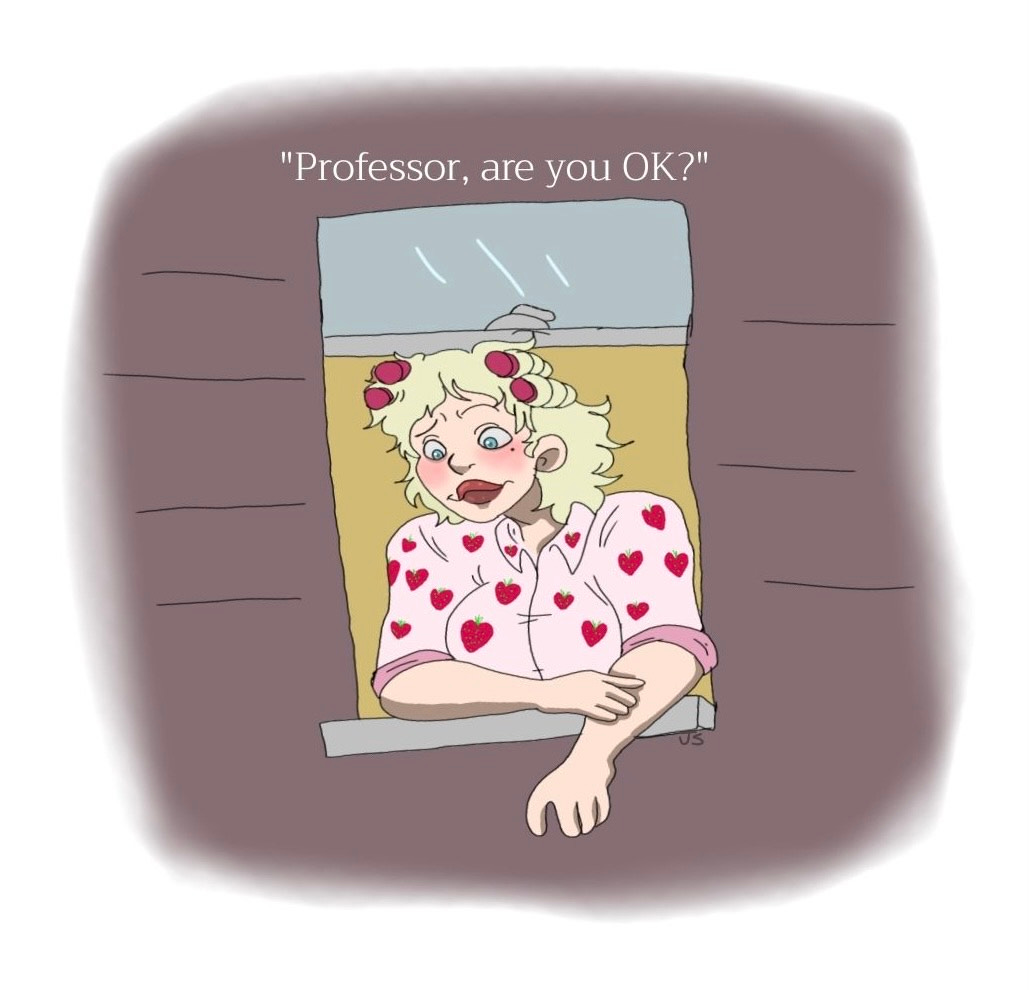

A woman leaned out a window perhaps twenty feet above my head and looked at me. I had never seen her before. Her blonde hair was in curlers and she had thick shoulders and a thick chest over which she wore a button-up dress patterned with strawberries. She said Professor, are you OK? Maybe you should get out of the street. I looked up at her, smiling. I had no idea how she knew me. I wanted to ask, but I was embarrassed. She seemed like a nice person, and I wanted to be a nice person, too, so I didn’t interrupt the flow of the conversation with what I imagine would have seemed like a hostile question. I told her I was out for a walk. Her face soured. Professor, is it such a good idea to go for a walk? I said I just needed a really quick breath of air and then I’d pop right back into my apartment. She was worried now: I had presented her with a problem she couldn’t solve. My son took your class six years ago, she offered, and he loved it. And he works at a nonprofit in Chicago now. They teach kids how to read. I told her that was wonderful and went back to staring at the brick wall of the abandoned apartment building. I was seeing sigils in the bricks: green, red, and yellow markings that looked vaguely like bass and treble clefs. I, too, was being presented with a problem I couldn’t solve. Please just be careful, she said. I nodded, still trying to decipher the markings, feeling her worried gaze on me. Finally I looked up to reassure her, but she was gone, having either left or never been there in the first place.

On College Street I still obeyed the crossing signals, waiting patiently for no cars to pass during the green light and crossing with no traffic during the red. College and Vandalia marked the beginning of what had always been referred to as the student ghetto, seven blocks of shoddily-constructed apartments operated by slumlords who lured freshmen in with the enticement of a living room bar and never told them about the black mold growing in the bedroom. In one of these apartments – a particularly large, ill-kept one – lived Ronnie and King. When I knocked on their door, King appeared in the window wearing a face mask and a baseball hat whose logo had been ripped off, the frayed stitching bent like exposed wire. He jerked his head in the window and I was unsure if I should jerk my head back. Then he disappeared and opened the door.

“The fuck you doing, Professor?”

“I don’t know. I thought I was on time.”

“On time? We’ve been waiting like three hours for you.” He stepped back to reveal Ronnie, who was also wearing a face mask and sitting on their half-destroyed couch, playing a videogame that looked like it involved the decimation of zombies. “Ronnie,” he said.

Ronnie regarded me. “Yo, you look like shit, Professor.”

I shrugged.

“If you wanna come in, you gotta wear this,” King said, handing me a face mask.

I put it on and stepped in. My breath fogged my glasses. Ronnie turned his console off and flipped the channel to the news. A local anchorwoman’s lips were moving, but I ignored what she was saying. The crawl beneath her image read: Death count spikes to over 450,000.

“Fuck,” Ronnie said, and then flipped open his phone and flipped it closed again.

King pulled his face mask down to smoke a cigarette, eyes never leaving the television. I watched with them. I wanted a cigarette, too, but I never asked them for anything unless they offered it to me.

“This shit is tragic,” King said, almost under his breath. “Ain’t it tragic?”

I nodded. King had bigger eyes than I remembered him having, big, tear-filled eyes. He was probably somewhere between 24 and 26 years old, but I saw him as someone much younger. A teenaged boy.

“Are you crying?” I asked him.

He looked at me like I’d just threatened him. “No, man,” he said, softer than I’d expected he would. “I’m not fucking crying.” He looked down at his feet, then back up at the TV screen. “You want a cigarette?”

He lit the cigarette for me like I was Lauren Bacall and he was Humphrey Bogart.

“They’re saying that there are like basically four categories,” Ronnie said without looking up from the TV. He had turned his console back on. “There’s you die right away when you get exposed to it, that’s the most common one. Then you die in like twelve hours – ”

“Six to twelve hours,” King said, in the tone I’d once used to correct students.

“Yeah,” Ronnie said absently, manipulating the control with particular intensity. “And then you’re symptomatic and it takes forever to die. And then if you’re lucky you’re a carrier and you live. There aren’t many of those.”

“No symptoms,” said King in the same paternalistic voice.

“Fuckton of our people got symptoms,” Ronnie said. “Losing money because these fuckers are dying so fast.”

King took a drag on his cigarette and looked at me. “You doing OK, Professor?”

“Yeah, I’m good,” I said.

King smiled broadly. “He’s good,” he said to Ronnie.

Ronnie laughed a braying laugh. I had always liked how it sounded. “Dude, you’re good! Ain’t you supposed to be thinking about grammar?”

I watched him decimate a group of female zombies who appeared to be moving in unison. “Not really,” I said.

“Hey man,” King said. “You wanna have a beer?”

I was tempted – I almost said yes – but Ronnie abruptly quit his game and stood up. “Not sanitary,” he said. Then he went into the kitchen and came back with the 20 bags taped together and handed them to me. I put the bags in the big inner pocket in my coat. “That’s a gram of China White right there, OK?” he said. “You have some social calls to make, Professor.”

I tore the face mask off the minute I left their apartment and flung it in the bushes out front, then flicked what was left of my cigarette onto the pavement. The sky was bruise-purple, darkening by the minute. I walked south on Vandalia and turned onto Houghton. Everyone lived within a fifteen minutes’ walk of each other: Cleo, the Davises, Brett and Anthony, etc., etc. “You’re like the bravest person alive,” one of them said, I don’t remember whom, taking my hand in both of hers as she gave me her cash. She wore Latex gloves. “I mean it’s kind of selfish of me to want you out there right now but at least you’re getting paid, right? And you don’t have to worry about any cops.”

It was dark and even colder by the time I finished. I walked back up College towards the little roundabout that would take me to my own place. Or Satchi’s, rather. Our place. The sigils had begun to appear on the street, illuminating a footpath ahead of me: one, two, three, green, purple, pink. The other colors changed, but there was always green. What was the pattern? What did it mean? Years ago, when my son was a child, he had held up a magazine in which an old Yoruban woman in a red wrap was pictured with her head thrown back, her eyes closed, necklaces of cowrie shells draped across her chest, smoke billowing from a bonfire behind her. She wore an expression of simultaneous fear and ecstasy. “What does it mean?” my son had asked. I had begun to explain Santeria to him and he had interrupted and said, “No, daddy. What does her face mean?”

I walked in to find Satchi sitting at the card table in the kitchen counting small bills. She smiled when she saw me. “Jellyman! What’s good?” I felt myself able to breathe easier than I had been outside. There were no sigils on the floor or the walls. I put the China White on the table and she laughed.

“OK, yeah, long day, huh?”

“Long fucking day,” I said.

“Jellyman,” she said. She had started calling me that because I am partial to jams and jellies at every meal, with cheese or bread or fruit, always have been. And though I prefer preserves, I started to eat Smuckers Strawberry Jelly with Satchi because she preferred it – ironically, it’s all we can get anymore. “Dude, Jellyman, you look destroyed.”

I folded my hands on the table and sighed. “I’ve been walking, I guess. And I didn’t sleep much last night.”

“I didn’t either,” she admitted tenderly. “I think maybe we should go easy on the uppers. We also don’t have that many of them left.” She put the last bill on the pile and frowned. “What took you so long? Why didn’t you beep me?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I tilted my head to one side so I could see the picture hanging crooked on the wall behind her: Madonna in a black chiffon dress, her elbows raised and her hands folded over her mouth. It was an awkward pose and an inexplicable photo, but Satchi loved it.

“Well, OK, just be careful,” she said, adjusting the strap of her bra beneath her tank top. “I don’t want you just disappearing and then turning up in like a lake or a ditch or something.”

I turned to make myself a bologna sandwich – we were out of sliced cheese, so I compensated with extra mustard – and turned back around to find her watching me.

“Seriously,” she said. “Like people who used to, you know, run this place – they’re disappearing. People who’ve caught a few cases.”

“OK,” I said. “I don’t run this place, though. And I haven’t caught a few cases.”

“Fuck it, dude.” She fanned her bills out on the table. “Have just like a little respect for my friends.”

I wanted to ask if they were really her friends, but I refrained. Instead I made her a bologna-and-mustard sandwich and set it down next to her stacks. Then I folded the paper over, flipping past the news in search of the Tuesday crossword. When I looked up, she had eaten the sandwich and taken the bag into the next room. I followed her and watched her cook some. Then I tied her off and tied myself off.

Afterwards, flush and slumped into the couch, the sigils phosphoresced behind my eyelids, shapeshifting: the clefs, then vases, then balloons, then fireworks. I thought of a Blake poem: Little Lamb who made thee / Dost thou know who made thee / Gave thee life & bid thee feed / By the stream and o’er the mead. It seemed someone was saying it to me, singing it to me. Was it Satchi? It wasn’t Satchi: she had stood and was shuffling to her bedroom, saying Goodnight, Jellyman. Try and get some sleep for once. It wasn’t anyone.

* * *

Months after we’d started dating, my wife told me that sugar was going to rot my teeth. Later on, she told me that the sugar was the first sign of my problem. No matter how respectable the method of delivery – pies, biscotti, preserves – I could never seem to get enough of it, my furnace-like metabolism incinerating it and craving more. It was the sugar that was the canary in the coalmine, not the partying. She told me she should have seen it coming.

I didn’t spend long on the market before I got the job – a tenure track job in a well-regarded English department, so hard to get! – and it wasn’t long after that until Spenser was born. He was one month premature and barely slept. The doctors told us this was a sign of intelligence. And in Spenser’s case, they were right.

In 1988, when Spenser was six and I was about to get tenure, I took a trip with him to my father’s sorghum farm. My mother had died the year before and my father was lonely and I think pleased that I had found a permanent job in the Midwest, closer to him than I had been when I was in grad school. My wife didn’t want to go for whatever reason – even then she had begun to withdraw from me, to recoil when I tried to kiss her in the morning, to refuse my offer of milk in her coffee – and I think this bothered Spenser, but he did his best to conceal it, smiling hopefully and singing along to the bluegrass tapes I played in the car. When we arrived, my father had already cooked a feast for us: a tender pot roast, butter-roasted sweet potatoes, a rhubarb pie. Spenser fell asleep at the table and I had to carry him upstairs.

My father promised me that night that I could take Spenser out on the tractor the next morning. I had been trying to quit drinking – to quit everything, really – since Spenser’s birth, but I woke up that morning and for reasons I don’t understand (or do understand, but would prefer not to) had three glasses of my father’s brandy and five bumps of cocaine. And I got behind the wheel of the tractor with Spenser next to me, ran over a giant rock, lost control, and rammed the machine into the side of my father’s barn. I remember Spenser’s face as we collided: incredulous, terrified, like an experienced equestrian who’d inexplicably lost control of his prize-winning horse. When we finally stopped, I slumped over the wheel, breathless with pain. Unharmed, Spenser shook my shoulder and screamed Dad are you OK? Are you OK?

I was awarded tenure and spent that summer in rehab. It was useless, because I’d slipped a disc during the crash and been prescribed oxycodone as a pain reliever. Every morning, while the rest of the patients took their medication for anxiety and depression, I took five milligrams of oxycodone and sat through breakfast and group blissfully high, got another dose at lunch and did the same thing until my final dose in the evening. The authority of my doctor was incontrovertible: as long as he was prescribing the drug and I was taking it in scheduled, moderate doses, the rehab didn’t count it as using. I had found my higher power. I could do all twelve steps without flinching.

When I got back to teaching, my movements were slow, warm, exquisitely dull. It was as if I were wearing baseball mitts on both hands and my head was wrapped in gauze. When I stood at the front of my Intro to Modernism class to talk about Anna Livia Plurabelle, I found I could barely say the name without laughing: my students laughed, too, finally given permission to express their disdain for James Joyce. My back was healing but the “pain” was getting worse and worse: my doctor increased my dosage to ten milligrams, then fifteen, then twenty. For a few years, I thought I was functioning at the peak of my capacity, writing a monograph on Nightwood and teaching Spenser how to play chess and cooking eggs Florentine in the morning – but apparently I wasn’t, or my wife said something, because my doctor caught on and cut me off.

I was desperately sick, hospitalized, discharged. I revived my old connections: it was unsurprising to find that the same people selling cocaine to middle class buyers were also selling oxys to the same set. They say the problem with people like me is that one is too many and a thousand is never enough. There are so many things to be said about people like me. Of me alone it can be said that I didn’t stop using when my wife discovered I was draining our bank account. I didn’t stop using when I missed four car payments and two mortgage payments and my wife had to work overtime to dig us out of debt. I didn’t stop using when Spenser came home from school early and found me snorting lines off the cutting board in the kitchen. I didn’t stop using when, at age twelve, Spenser announced that some kids at school had seen me nodded off in the park and were calling me Professor Junky and that he was disgusted with me and couldn’t wait to get out of my house. I didn’t stop using when a student told a colleague of mine that I’d been buying drugs off his friend, who happened to be in my Gertrude Stein class and getting an A, and word got to the dean, and I was informed that things would “become very difficult” for me if I didn’t resign from my position at the end of the semester. And I didn’t stop using when my wife divorced me and she and my fourteen-year-old son left me for a different part of the country, she wouldn’t tell me where, only that she would file a restraining order if I tried to follow them. By then, of course, oxys weren’t enough.

Satchi – with the crooked front tooth, the tangled hair, and the thick eyebrows – had been just a freshman when she lost her scholarship at the university due to failing grades. She was a bright first-generation student estranged from her family. She’d stuck around because she was making good money selling drugs to people like me. When I lost the house, she let me move in. She had been a biochemistry major, which was likely what Spenser ended up being: at 21, she was four years older than him and just as smart. And like Spenser, she was double-jointed and loved the outdoors. Unlike Spenser, however, she had patience for me, tolerance for my dissertational ramblings, my philippics against the federal response to the virus, my pathetic need to shoot up. She had similar feelings, similar needs, though in her these needs seemed less pathetic than reasonable reactions to a dire situation. I cared very little what happened to myself, but I cared what happened to her. I wanted her to clean up and try and work for the CDC; I told her often that she was the one with the brain to get us out of this mess. She said, Jellyman, you never stop with the Dead Poets Society shit, do you? She liked that I tirelessly helped her move her product in addition to Ronnie and King’s, that I got her free stuff from Ronnie and King, kept us subscribed to the New York Times (which still printed, against all odds), paid the utility bills, kept the apartment (somewhat) clean, and cooked meals when I could out of what I could. I was a comfort to her. I once told her how sorry I was that capitalism had destroyed the planet and that I had destroyed myself and how I really thought young people like her deserved better. She gave me a hug and said Pops, you’re crazy. I remember this because it’s the only time to date that she’s called me “pops” instead of “Jellyman.”

The crawl on Fox News read Y2K come early? Experts debate. I was having two eggs and some cocaine, some of the worst cocaine I’d had in my life, when Satchi came into the room in her slippers and bathrobe. She looked at the TV screen and scowled. “Change the channel,” she said.

“It’s good to know what the opposition’s up to,” I said.

She grabbed the remote from the coffee table and flipped the channel to a cartoon show, Daffy Duck getting hit on the head with a hammer and growing a fleshy horn. Then she got a bowl of Cocoa Puffs from the kitchen and sat down next to me.

“Someone shorted you,” she said. “We came up fifty short.”

I did another line and kept watching the cartoon.

“You have to go get that money,” she said.

I hated when she was all business. She seemed so committed to her current reality in these moments. Like she was never going to get out and go work for the CDC.

“How do I know who?”

She clucked her tongue. “Come on, Jellyman. You know who.”

A guy across town, Gus, who, like a lot of the richer junkies, was not only very much alive but living in a rambling, generations-old house he’d inherited from his parents. He bought everything from me, Satchi’s and Ronnie’s and King’s stuff, and he required deliveries almost every other day. He was a relatively new customer, a huge source of income, but he wasn’t always reliable. I hated looking at him because his face was the hollow ghost face everyone’s used to seeing on TV, the collapsed-vein face, the dead-man-walking face. I didn’t even go inside to give him his deliveries, just palmed them to him on his front porch. More than once, he’d come up $15 or $20 short: I always missed it because I’m something of a dyscalculic. This was the most he’d ever shorted us, assuming it was him.

The walk was a long one, and I had to pass through the pedestrian mall, the place where children usually gathered in the summer to play in the fountain, where students drank in sports bars and faculty drank in gastropubs, where the town’s upper crust shopped for organic food. Everything was shuttered, the mall’s patrons at home with their closets full of toilet paper and non-perishables. A couple homeless corpses lay splayed across the mosaic of brick, practically nothing more than viral loads. I put my shirt over my nose and kept my distance from them. I looked down at the brick expecting to see the sigils and saw that they were in fact lines and curves, green and pink and grey and white, building something bigger than themselves. I stood back and watched them play, scatter, swirl. Then they coalesced into a pattern. A gorgeous pattern: Spenser’s face, aged six, cowlicked, mouth open in a guileless smile. I stood for an instant with my shirt still over my nose, my eyes itching, my hands balled into fists, as Spenser’s face shook and vibrated and blinked and then dissolved. Little Lamb who made thee.

My wife’s family lived in Seattle, but she wasn’t particularly close to them: her father had been an abusive alcoholic and her mother had spent most of my wife’s childhood asleep. Other than Seattle, though, I couldn’t imagine where they had gone. My father’s farm was too close and too obvious, though she did have an ally in him: he hadn’t spoken to me since I’d wrecked his tractor and his barn. This would be Spenser’s first year of college. Had he been allowed to stay on campus? Had he chosen to? I had read about students who remained, either fearful of returning to high-conflict homes or staying to protest the government’s mismanagement of the pandemic response, the president’s disregard for the WHO’s warnings, the lack of hospital beds and testing kits for the homeless and addicted. He would have had one month of instruction, maybe two, before the virus made it to the States. I thought these thoughts every day, obsessively, but only let myself do so for an hour at most. If I gave myself any more time, I couldn’t make it through the day.

Satchi called me: You get the money? I said: Almost and then Gotta go. What did that mean, I’d “almost” gotten the money? Either I’d gotten the money or I hadn’t. My semantic ability had been deteriorating for the past three years – it was hard for me not to notice it, even if no one else was. The sun seemed to be moving fast in the sky, an entire day elapsing in seconds. I could see my breath in the air, looking like plumes of smoke. A single car crawled past me on the road, the driver a woman in sunglasses and a face mask. She turned to look at me and I looked at her and waved. She turned back to the road, increasing her speed.

I rang the doorbell several times before Gus came to the door. He wore a t-shirt and jeans, face and hands bare. He was unshaven and odorous. I looked at his feet out of politeness.

“Gus, we were counting and we think you shorted us.”

I ventured eye contact and saw his empty stare, his sawfish-thin face.

“Can you just do this so we don’t have to get into it? I’d rather not make a whole thing out of it.”

A smile quivered into existence at the center of his bottom lip and spread with excruciating slowness over the rest of his face. “Sure thing, Professor.”

I smiled back. This was easier than I had thought it would be. I watched him pad into the dim room behind him. I looked over my shoulder, at the sky, the fuzzed-out sun. I thought of Milton: Thou sun, of this great world both eye and soul. I thought of teaching Paradise Lost, of a student who had come into my office hours to discuss her Catholic family and their “fallen angels”: her aunt who was in jail for shooting her ex-husband in the shoulder, her cousin who’d robbed a convenience store. She had wanted to write a book about them.

When Gus returned, he was moving with uncharacteristic quickness, pointing a gun in my face and showing me a badge.

“DEA,” he said. “You’re under arrest for the possession and distribution of schedule one narcotics.”

My vision constricted. I raised both my hands. Cops still. I hadn’t realized there were cops still. At any point, I expected him to lower the gun and smile and tell me he was playing an elaborate and unfunny prank. But he didn’t. His eyes narrowed. I opened my mouth and from it came a strange squeak that sounded barely human.

“Get inside,” Gus said, jerking the gun in the direction of the foyer.

I obliged. Inside was a tableau I could never have expected: a wiretap, a CB radio, several tape recorders, and the special helmets government officials wore in highly infected zones. Something about the equipment looked shabby, pirated – the helmet was heavily dented and scuffed and the CB radio’s microphone looked to belong to a different machine. At Gus’s feet were two large canisters with hoses, not unlike fire extinguishers, which looked to have been emptied of their original contents and repurposed. He guided me onto the sofa and then edged over to a canister, picking it up and cradling it in the crook of his elbow.

“Do you know what’s in here?” He pointed with his gun to the canister.

I didn’t ask. I kept my hands up.

“Viral spray,” he said. “This thing’s already killing vermin like you naturally. We’re just hurrying it along.”

I nodded.

“If you try to get out of this, I’ll come find you, I’ll come find them. I know where these people live.”

My heartbeat became dysregulated, the breath rattling in my throat. Satchi.

“Who do you work for? Thugs moving heroin?”

I remained silent, terrified to ask who he thought the thugs were.

“Okay, don’t talk.”

He made me carry a canister and we piled into a nondescript Honda Accord. Gus was helmeted. Maybe it was the sigils covering the interior of his car, but I began to find him ridiculous. With his fake-junky face, the constellation of pimples at his neckline, his Target jeans: Gus was foolish, a boy playing at being a cop. He was ineffective, his mission insignificant and doomed. This will pass, I told myself. I will eat Twinkies and watch cartoons with Satchi tonight and send her off to bed before midnight.

Gus said something into his CB radio and another car appeared behind us. The driver of this car wore a helmet like Gus’s but looked older than Gus, more serious, bulkier, all of which gave me pause. My terror spiked again. I immediately wanted to know where we were going.

“Are we – ?” I ventured.

“It’s better if you don’t talk,” Gus said.

We pulled up, unsubtly, mercifully – not mercifully, what was wrong with me? – in front of Ronnie and King’s apartment. Gus forced me out of the car, and the second cop got out as well. Up close he looked even less like an actual cop than Gus did: he was more of a high school linebacker who’d wandered into an ill-fitting uniform. He and Gus nodded to one another. The three of us walked up to the door, myself at gunpoint. Before King could appear in the window, the second cop kicked the door in handily. Inside, Ronnie and King were playing a video game with a pack of racecars peeling endlessly around a track.

“Oh fuck,” Ronnie said, throwing his controller down on the floor. “Fuck!” He dove between the sofa cushions and produced a gun. King, on the other hand, was looking at me with disappointment.

“This dude was a fucking narc? For real?” he said to Ronnie, but I could tell it was really intended for me. He pivoted to me and spat on the floor. “I never trusted you anyway.”

This stung. Why couldn’t he see that I had never intended this? Embarrassingly, I was near tears. I wanted to say something to King about not being a fucking narc, to promise him that I wanted the best for him, that this would all be over soon, but before I could say anything, Gus announced that Ronnie and King were under arrest. At this point both Ronnie and King had guns trained on Gus and the second cop, who carried a metal canister of the exact same dimensions as the one I was being made to carry. I wondered stupidly how I had thought this was going to end. Why would I trust the world – the brutal, desolate, Old Testament world – to preserve myself, Ronnie, and King through this encounter?

“Drop the guns,” the second cop said, in a baritone much more intimidating than Gus’s.

“Fuck you,” Ronnie said, and shot the second cop in the knee.

The second cop crumpled to the floor, and as he did, he sprayed a dense, greenish mist from the cannister. Ronnie and King put their shirts over their noses and screamed the desperate screams of children with broken arms, bruised heads, skinned knees. I considered swinging the canister at Gus’s head but dropped it and ran into the kitchen instead. Nobody seemed to be thinking about me. Both Gus and the second cop were on the floor now, and Ronnie was fumbling to get their helmets off, and Gus shot King in the stomach and King let out a breathy groan and dropped to his knees, and Ronnie ripped the second cop’s helmet off and then did something to Gus’s neck that made him still, I heard it but I didn’t see it. And then they were all unmoving on the ground and the mist was hanging in the air.

My vision was blinking in and out, on and off. I sat on the kitchen floor, my back and head against the wall, imagining or seeing an angel standing in front of me with wings unlike those I’d seen in Renaissance paintings, wings like a bird’s instead, bony and fleshy and sharp-feathered. My pager buzzed again. How many hours had it been since I’d left Satchi? I inhaled deeply and prepared myself: might as well hurry it along.

* * *

An addict’s dreams are different from a non-addict’s dreams in that they’re full of desire, anticipation. Sleep isn’t rest, it’s planning: What will I do when I wake up? Where will I go? Who will I see? Will it end well for me or poorly? Whomever we meet in our dreams, however outlandish they look, there’s some real-world analogue. Our dreams, like our lives, are chess games and we’re pawns trying to get to the other side of the board. We’re always trying to get queened.

Except sometimes my dreams are different. Sometimes I see through a distorted, anamorphic lens the sigils, the fireworks, the blurs like city lights in a fog. And in the middle of it all, desperately shaking my shoulder, asking me if I’m OK: Spenser.

* * *

It was night. Somehow, it was night, and I was opening my eyes, and the room smelled putrid. I’d been paged twenty-four times, all from Satchi. I stood up and saw that I was still in Ronnie and King’s apartment, that Gus and the second cop were still there as well, that all of them were dead. And I was alive.

I stood up and stumble-ran like a panicked foal out the busted-down door and got in the Accord. Miraculously, the keys were still in the ignition. No one was outside to steal cars anymore. I started the ignition and the radio snapped on. Instead of CB cop chatter, I heard country music. Specifically, a song about a man who’d been beaten in a bar brawl. I turned the radio to the news: Sixty-seven more deaths reported in the county. One infected man, homeless, schizophrenic, and with several outstanding warrants for loitering, has died from the virus without any known contact with the other infected. Says local public school teacher Lacey Styven: “I just saw him sleeping in the park every day. People generally tended to avoid him.” I turned the radio off. I brought my shirt over my nose and then, remembering, pulled it down. So I was one of the asymptomatic carriers. There were only a few thousand of us in the country. According to the WHO, I was supposed to quarantine myself for fourteen days, at which point I’d be safe to interact with the un-infected.

I went back inside the apartment, into Ronnie’s bedroom, into the walk-in closet, behind his dress shirts where I knew he kept the bricks. I took three, figuring I could come back for more – unless they were raided, of course – and a bag of needles and ties as well. Then I drove back home and stood outside and called Satchi: Come to the window. The curtains shifted and there was her face, tear-streaked and puffy, her mascara crumbling at her eyelashes. She began to open the window but I yelled for her to stop.

“It’s not safe!” I shouted through the glass.

“What? What’s not safe?”

“Gus had the virus,” I said, my face nearly pressed to the window. “In canisters. He was a cop, and he had backup. They got to Ronnie and King. They sprayed it on all of us.”

Her eyes went wide. “Oh fuck, Jellyman.”

“I’m a carrier,” I said. It was gauche, but I found myself smiling at her amazement. “I’m going to go away, OK?” I explained that she was safe, that Gus and his backup were dead. “I’m going to be gone two weeks but I’ll be back after that. You know how it works, right?”

She nodded and rubbed her forehead with two fingers, a sign that she needed a fix. “I should never have sent you out,” she said. “Of course some shit like this was gonna happen.” Her eyes were shiny with tears.

“It’s fine,” I said. I put my hand to the glass. It was freezing, and I yanked it away. “Really, how were you supposed to know?”

“Fuck, Jellyman! I’m so sorry!”

“I’m going to go, OK? Check the front door in two minutes.”

Hurriedly, I dropped two of the bricks and some of the needles and the ties on our welcome mat. Then I got in the car and watched Satchi emerge from the house, Latex-gloved, to retrieve them. I waved at her and she waved back. She said something I couldn’t hear, a sad something, an apologetic something. In response, I mouthed beep me and began to drive away. In my rearview mirror, she stayed standing at the front door, tucking her unruly hair behind her ears. I didn’t want to know what she’d said.

* * *

The worst fate of all was that of the symptomatic: unlike those who died upon first exposure to the virus, the symptomatic suffered for weeks, developing lesions on their skin immediately, and then lesions on their lungs, lesions on their brains, internal hemorrhaging, and finally organ failure. The symptomatic who couldn’t afford to die in quarantine in hospitals or specialized treatment centers or among family members flooded homeless shelters, warehouses, and repurposed big box stores instead. The Walmart fifteen miles out of town had been overtaken by them, and that was where I went after I gave the bricks to Satchi.

There weren’t as many there as I had expected: forty, maybe fifty, left, the oldest ones given priority on makeshift beds and inflatable mattresses. Most of them looked to be over sixty, an age bracket I was creeping towards myself. None of them seemed to care that I didn’t share their symptoms – I imagine things like that don’t matter all that much when you’re staring down death.

I was given a bed to share with a man named Alan. Alan, who was well into his seventies, had a severely rhinophymic nose, weeping lesions on his arms, and a thick pair of plastic-framed glasses that reminded me somehow of the late-night talk show hosts of my childhood, though I couldn’t remember any of them actually wearing glasses. I fell into a nighttime routine with Alan – who described himself, appealingly enough, as a “lifelong learner” – where I would recite poetry to him, whatever I could remember (this turned out to be a somewhat motley selection of Yeats, Eliot, Dickinson, Brooks, Neruda, Bishop, Gibran, and Lowell), he would fall asleep amidst the bright lights and low rumble of activity in the bedding aisle, and I would sneak out to the Accord, which I had hidden in a copse of trees ten minutes’ walk from the Walmart, and shoot up. Then I would return to the Walmart, page Satchi, and fall asleep myself.

This lasted for over a week until Alan asked me over pizza Lunchables: was I addicted to heroin?

“No,” I said politely.

Alan smiled, causing his ruddy cheeks to touch the rims of his glasses. “Come on. You can be honest with me.”

I squeezed sauce onto the pasty dough disc of my unbaked “pizza,” considering how I should proceed. Alan leaned forward conspiratorially.

“When I came back from Vietnam, I started meeting guys like you. Addicts. Junkies, but that’s a horrible name, I always thought. A horrible word. I can spot one of you even when you look good. But you don’t look that good, son.”

I tilted my head to one side. My pager buzzed.

“Who’s always beeping you?” Alan asked.

“My student,” I lied. “An old student of mine.”

Alan made a silent ah face and turned his attention to his own pizza, which he had determined was in need of cheese. “I’m dying, obviously,” he said.

There was nothing to say in response to this, so I laid miniature pepperonis on my own pizza.

“And you know what? I always wanted to try it. Just once. I always wanted to see what’s so good about it that people would throw their homes and their families and their money away for it. But I knew if I tried it I’d become just like one of you.”

“That’s not exactly true,” I said, and then bit my tongue, frustrated that I’d given myself away.

“Oh?”

I sighed. “It’s not just – it’s not necessarily just, like, you’re automatically hooked.” The unmistakability of my need was making me inarticulate.

Alan placed a lesioned hand on mine. The temptation to recoil was nearly unbearable, but I managed not to. “Let me try it,” he said. “I’m going to die soon anyway.”

So we went out to the Accord, Alan’s arm around my neck, the two of us walking slowly, crookedly, as if on broken legs that had healed incorrectly. The moon made a silver terra infirma of the ground before us and the air was dense, windless, deoxygenated. I felt momentarily as if I were walking on another planet. We were astronauts. But not really. Really, we were two men, one old and the other much older, making their way to a car full of junk.

Alan watched me cook, which, had I not been as advanced in my habit as I was, would have been difficult to do in the Accord. Then I tied him off – his veins were enviably plump and un-tampered-with – and tied myself off and shot it and we leaned back into the seats and there came the warmth, the spectral flood of warmth, and then silence except for Alan’s stunned panting, the sky sparkling through the Accord’s sun roof.

“Alan,” I said. “How does it feel?”

I looked over at him and saw him blinking behind his glasses, grasping the injection site at the crook of his elbow.

“Alan,” I said. “Listen to this: I sought a theme and sought for it in vain / I sought it daily for six weeks or so / Maybe at last being but a broken man / I must be satisfied with my heart…”

Alan was silent, blinking, breaths coming shallow. Then he croaked, “Although.”

I smiled. “Very good. You remember this one. The rag and bone shop of the heart.”

“Although winter and summer till old age began / My circus animals were all on show.”

I wanted to praise him but I couldn’t find the words, my mouth cottoning, my muscles going slack, my face losing its contours. I closed my eyes and listened to Alan breathe until he wasn’t anymore.

* * *

I woke up shortly after dawn to find Alan wasn’t next to me. He wasn’t collapsed facedown outside the Accord, and he didn’t appear to be in the Walmart, either. The sigils were, though: radiant and tropic, tilting towards the fluorescent lights on the Walmart’s ceiling. I walked down the aisles trying to ask about Alan but nobody seemed to have seen him. Nobody seemed to be in the aisles, either. Everyone was in the electronics section, watching the wall of TVs.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” a lesioned woman turned to me and gestured towards the TVs. “What the young people are doing?”

A helmeted reporter stood on what looked like a campus quad, surrounded by young people in face masks and Latex gloves with signs that read DIVEST FROM BIG PHARMA and SUPPORT THE UNINSURED. We are here, the reporter said, on the University of Michigan campus, where a protest has broken out among students over what they’re calling “a systemic failure to respond to a national crisis.” Students all over the country are refusing to leave campuses until testing and hospital beds are made available to the homeless and uninsured.

Now the reporter was speaking to a girl who looked to be about Satchi’s age: There are people on the streets, who are disproportionately minorities, dying at a way faster rate than other people –

Don’t you think that’s because other people have been able to afford the resources to keep themselves safe? the reporter interrupted.

The girl looked caught off guard, like she had been lured into some kind of rhetorical trap. Yes, I think so, she said, a bit warily. And I think we need to give people on the streets the same resources others have.

I watched B roll of the students marching in a circle with their signs and chanting, the girl who’d been interviewed addressing all of them through a megaphone. And then the camera cut to a second interview with a young boy, blue-eyed, shaggy-haired, his face mask betraying the outline of a Roman nose. When he spoke, I knew his voice instantly, the way it had been before it had become a baritone. It was Spenser.

We have to show some compassion, Spenser said. We can’t just let the death count keep creeping up while we only think of ourselves.

He was looking directly into the camera, his speech measured, his gaze confident. My ears began ringing. I drew a quick breath and stepped back.

“Are you alright?” the lesioned woman asked.

The reporter looked ready to speak, but Spenser seemed determined not to let himself be interrupted as the girl had been. We have been monitoring the situation around campus and have reason to suspect that certain members of the police force – those who remain active at least – are somehow spreading the virus to addicts and the homeless, especially members of those populations with criminal records. He turned to the reporter, who seemed too stunned to interrogate him further.

I inhaled deeply and shook my head. I was flushed now, but not the good kind of flushed. I was embarrassed by myself. Mortified.

“Yes, such impressive kids,” I said, and dug my hands into my pockets.

The lesioned woman nodded and returned her gaze back to the screen, on which my son was saying: The time to act is now.

* * *

When I returned to Satchi on the fourteenth day, it was with two trays of cookies, a Walkman, and the makings for several peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. She hugged me and poured me a glass of chocolate milk and asked how my time among the zombies had been. I made a ghoul face, rolling my eyes back in my head and sticking my tongue out at an angle, and she laughed. I didn’t tell her about seeing Spenser on TV.

“I actually moved a lot of molly while you were gone,” she said. “There are these frat boys having, like, plague parties. That’s what they’re calling them.”

“They never left their fraternities?” I asked, slathering a slice of bread with peanut butter for her.

“Yeah, no, I guess not. And like they’re basically just sitting in there rolling and getting all kinds of fucked up and being like ‘If I die, I die.’”

“Wow,” I said. And then, wanting as always to better speak her language: “Damn.”

I served her the peanut butter and jelly and watched her peel the crusts off and take a bite. “Dude, Jellyman, of course you put on too much jelly.”

I bit into my own: she was right, I’d skewed the ratio. My body relaxed at the surge of sugar. “But it’s not that bad, is it?”

“No, it’s not that bad.”

We ate in silence, and when she finished, she stood and grabbed her hoodie from the table. I saw that it had been concealing a small handgun.

“Satchi!” I said.

She grabbed it and stuffed it into the back of her jeans. “A friend got it for me,” she said.

“Give it to me.”

“No.”

“Satchi,” I pleaded. “Why do you need a pistol?”

“Jellyman, why do you think I need a pistol? You almost got killed.”

“OK, I almost got killed,” I said, walking slowly towards her, my palms upturned as if this would make her hand it to me. “So shouldn’t I be the one with the pistol?”

“Dude you’re an old fucking man,” she said, shrugging away from me. “I’m gonna keep us safe.”

I sighed. I would pick my battles. “Fine,” I said. “I only ask that you please keep it locked in the safe in your room.”

“Yeah, fine.” She slunk into her room and shut the door.

When she came out an hour later, I was doing the Sunday crossword, trying to think of a twelve-letter word for “forgotten memory.” The gears in my brain were turning slowly: it wasn’t until Satchi had plunked herself down next to me on the couch that I remembered “cryptomnesia.”

“You wanna roll, Jellyman?” she asked, showing me two pills.

The acuity of yesterday’s embarrassment intensified: my son healthy, and a man, and fighting for change – everything I had always wanted – and I was in a roachy apartment about to roll with Satchi. But I didn’t want to disappoint her after having left her alone for so long.

“Sure,” I said, putting down the paper.

On the morning Spenser and my wife left me, while my wife was on the phone with her lawyer in the next room, Spenser had stood before my slumped and bedraggled form on the couch, hands on his hips while I held my head in my hands.

“Why do you do it?” he asked me. “Why do you keep on doing it?”

I didn’t know what other to tell him other than the truth: “To feel good.”

He crossed his arms and sighed. “Isn’t the way you normally feel good enough? Can’t you just be OK with the way you normally feel?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I really didn’t.

“What do you mean, you don’t know?” His voice was rising. “Like after all this, you don’t know?”

What my son couldn’t understand – but Satchi and I and the frat boys and Ronnie and King and all the recipients of my deliveries could – was that feeling the way you normally feel is settling for mediocrity. Why feel one way, one dull way, one sad way, when you could feel the best you’ve ever felt in your life? And that was how I felt for a few hours that night, dancing with Satchi to her favorite Backstreet Boys album, eating single Cocoa Puffs at a time, giggling manically at cartoons. She told me about her favorite memory, of her big sister driving her to a carnival and passing a cheese sandwich to her in the backseat. That’s all Satchi could remember: her sister’s thick hair in the wind, a concertina on the radio, unwrapping the cheese sandwich – nothing about the carnival itself. I told her about being a kid and fishing in the creek on my parents’ farm and catching a trout big enough for us all to eat. She called me a boring old white dude and I said Guilty as charged and made us both peanut butter and jellies that we didn’t eat, just kneaded into a brownish-red paste on our separate plates, rhapsodizing about the texture the entire time. Then, when we were both pale and low on serotonin, we gave each other a perfunctory hug and said goodnight and dropped off to sleep in our separate bedrooms.

What I couldn’t possibly know as I slept was that I’d come home too early, that the WHO had underestimated the power of this thing, or at least my individual power to carry this thing, that the virus was still in my bloodstream and now in Satchi’s, that the hug had done it, or the peanut butter and jellies, that I hadn’t washed my hands enough, or had coughed without realizing it, that she’d inhaled pathogens that were now making short work of her airways, clotting up her blood, stunting her heart. And when I knocked on her door the next morning, worried that she hadn’t come to breakfast, and then pounded, and then shoved it open with my shoulder, I would see firsthand what I had done.

* * *

There is a commonly held perception that we don’t grieve, that we just slide the watches off the wrists of our dead and pawn them to get our next fix. This couldn’t be farther from the truth. I have spent years of my life standing at the heads of classrooms, making the case for actually giving some thought to being human. I have argued for the humanity of Bertha Mason, of Queequeg, of Miss Havisham. Why not argue for my own?

Yes, I ran from the bodies of Ronnie and King carrying bricks of heroin like the junky I supposedly am. But I would have stayed and dressed those bodies, cleaned those wounds, closed those eyes, if I would have. Had I not been scared, had I not been desperate, had I not been in a state of simultaneous shock and humiliation, I would have stayed.

I didn’t leave Satchi’s bedside until sunset, when I went to the kitchen to get water and soap to wipe the vomit from the corner of her mouth. I wrapped her in her favorite bedsheet, one with pink and peach stripes, and then brought the sheets she had been sleeping on into the backyard, where I set fire to them. Then I began digging a hole. No one came out to question me. By 2:00 in the morning, I had finished. I emptied the pistol’s chamber and wrapped it in the sheet with her.

Why is it that I can only be human when I’m picking my son up from daycare or publishing a monograph or buying earrings for my wife? Why can’t I be human in this moment, too: shoveling the dirt on top of Satchi-but-not-Satchi-anymore, collapsing on all fours and screaming and sobbing, drinking half a bottle of bourbon? Why can’t I be human in the moment that I cook far more than I know I should, when I inject it all between my toes because the veins in both my arms are collapsed and the skin is becoming infected? Why can’t I be human when I fall face-first to the floor, my heartbeat loud all over my body? Why can’t I be human when I think of Satchi and then Spenser and remember them how they never were, as toddlers playing together in a sandbox, me watching them, smiling, encouraging them to share?

My brain did a strange thing when it realized my body was failing: it showed me a field of grain, golden stalks lolling in the wind, and it said: This is how it looked before you were born. And when I asked what “it” was, my brain said: The world.

* * *

I was awake, covered in my own vomit and piss. My heart was thumping into the floor’s peeling clapboard. My eyes saw the room as a collection of semi-geometric blurs, then shapes, then objects. I sat up and clasped my hands together, tight enough that I felt pain. I slapped my thigh, wet with piss. I took off my jeans, also wet with piss. I coughed up a few more chunks of vomit. Dreams lacked this amount of sensorial detail. The afterlife – my afterlife, especially – wouldn’t be this banal. I had been preserved somehow.

Miraculously, I had never before near-overdosed, so I had never had the chance to observe what the world looks like after. I can attest that there is nothing like it. The shower, normally squeaky and unreliable, felt luxurious. My clean clothes – an old flannel and a pair of ratty jeans – felt silken, stitched to meet my measurements like the garments of a king. The egg I scrambled was soft and warm, the cheese I mixed in thick and creamy. I was a wretch who had killed Satchi and lost my wife and son and somehow led the cops to Ronnie and King and I did not deserve to be alive. But here I was, alive.

I sat in the kitchen among our things – Satchi’s backpack and Madonna photo, my unread newspapers, the stacks of bills we’d racked up, the scale and bricks and wraps and powders on the kitchen counter. The sun was grey-yellow in the upper rightmost corner of the window. There was an Earth and it was still turning against all odds.

I flushed everything we had, guilty that I was polluting the water table with opioids and amphetamines but too full of adrenaline to stop. I drained our liquor bottles and dumped the needles and ties in the dumpster behind the complex. I had seen Trainspotting, and I had seen people worse off than the guys in Trainspotting: I knew what awaited me in the next twenty-four hours. I would prepare myself for it somehow. I lit one of Satchi’s cigarettes and took a long drag. I finished it and smoked another. Then another.

I began to pack a bag of clothes and money. I thought of Spenser saying that that time to act is now. He was right. Of course he was right, with his self-assured eyes, his confident baritone. The time to act is now, I told myself. There would be a future, and maybe he’d be president in that future. Not president – what has any president ever done for us? He’d be like a tree growing out of fresh soil, he’d be a snatch of joyful song overheard on a city street – maybe he'd be a thought more and more people start having until we’re all having it, collectively, happily. The time to act is now.

By the time I got into the Accord, I had smoked the entire pack and was starting on a second one. I looked at the sun through the sun roof: no longer muted by the apartment’s dirty windows, it was brilliant – a cold, bright winter sun. It was wrong, of course, that I should be the one seeing this sun. But many things were wrong, and I didn’t want to make an accounting of those things anymore. I touched my fingers to the sun roof’s glass and whispered an apology. To whom? Too many to name. Just say “the world.”

I began to drive. I would be in Michigan by sundown.

Thank you for reading!

If you enjoyed this story, keep your eyes peeled for its novelization: coming to bookstores near you in the next 5-6 years!

If you enjoyed the illustrations, please give Jamie a follow on Instagram (where they’re also accepting commissions), like their page on Facebook, and/or buy them a coffee!

Finally, please enjoy this impromptu portrait Jamie drew of me when I came to speak at their college — the beginning of our artistic collaboration!