The Muppet Christmas Carol: A Jolly Exegesis

Lessons learned from Charles "Gonzo" Dickens starting in 1996

If you were to ask me which 90s media properties first instilled in me a sense of storytelling-as-magic, The Muppet Christmas Carol would be at the top of that list. Even if you didn’t ask me but nevertheless found yourself alone in a room with me during the latter half of any given December, you’d get an earful about it. You’d hear how incredible it was that the Muppets’ anarchic, wisecracking energy was harnessed for a purpose as humane as the spiritual conversion of penny-pinching Malthusian nihilist Ebenezer Scrooge. How spellbinding it was that Michael Caine – then in his middle age and preparing to enter the final act (or “stave,” if we’re being Dickensian about it) of his nearly seventy-year career – played that Malthusian nihilist with such rage-choked sincerity that you would have thought he was sharing a stage with Kenneth Branagh instead of Kermit the Frog. And most importantly, what it felt like to be six years old and watching that film for the first time, to see the Dickensian project – i.e. the social novel as anti-industrial clarion call – brought to life by literal Muppets. Subscriber, that movie is nothing short of a revelation.

For me, the greatest pleasure of arguably the greatest Muppet film is Gonzo’s narration. Brian Henson, who directed the film at 28 shortly after his father Jim’s passing, wanted the unlikeliest Muppet to play Charles Dickens and so cast droopy-lidded Gonzo, who at that point was probably best known for his Andy Kaufman-esque performance art. But Gonzo-as-Dickens was not a casting choice that was played for laughs. He was effectively remade, sagging puppet-eyes widened so as to convey, according to the voice actor who played him, a “zany, bombastic appreciation for life.”

Though Gonzo journalism was not named for our Great Gonzo[1], watching him play Dickens might lead one to suspect that it was. Indeed, as someone who was to grow up to spend much of her life writing fiction, it was absolute catnip to be introduced to “Charles Dickens” – and thereby the concept of “great social novelist” – not as a distressed young man trying to pay off his father’s debts in a boot-blacking factory, nor as angsty hopeful savior of the Victorian working class, but as a blue-feathered beaked creature who follows Michael Caine around a facsimile of 19th century London, dictating everything that will happen to him moments before it does. And this was not the tubercular, gangrenous, rutting-in-the-streets London the actual Dickens would have known, with its corrupt judges and a-better-world-awaits-us Christianity and overfull debtor’s prisons. No, this was a Currier and Ives kind of London – London as we Americans wanted to see it: gaslit street lamps and charming cobblestone streets and the playful suggestion of a theft-free open air market, the kind of place where one would not be surprised to see Kermit the Frog ice-skating, nor pigeons breaking out into song. No pledges to Queen and country here, no anxieties over the advancing diminishment of the British empire: just pure wonder.

Like many a millennial weirdo with a media affinity, I was typically more inclined to the wisecracking sidekick of any given story than the hero or even the villain, always rewinding the VHS to remind myself what Aladdin or Jafar had just said because I was so distracted by Robin Williams’s immortal turn as Genie or Gilbert Gottfried’s on-the-nose squawking Iago. Rare was the film when I was actually inclined to pay attention to the narrator, but Muppet Christmas Carol was such a film, and pay attention I did. Even the sidekick was paying attention: whenever Rizzo the Rat gets up to something, it’s as a direct result of being along for the insane ride that is Gonzo’s narration. And Rizzo doesn’t really have time for extracurricular antics, because he must be coached through the suspension of his disbelief (A blue furry Charles Dickens who hangs out with a rat?!), then witness Gonzo’s “godlike” superpower to know precisely what’s about to happen moments before it does, then become deeply invested in Scrooge’s redemption. By the end of the film it’s clear that pieces of the story have stuck with him and changed him: he’s transformed no less than the rest of the cast. One might be so bold as to call Rizzo not a sidekick, but a reader.

That Gonzo could go from being a fringe showbiz type in a cheap velour suit to author of The Pickwick Papers was a formative lesson for me. People become authors, but authors never cease to be people,[2] which means that we could all be godlike and foible-ridden at once – that is, the only barriers between ourselves and making art we love are formed of our own self-punishing beliefs. Gonzo isn’t just confident as Dickens – he knows he has a job to do, and wastes no time in becoming the Virgil to our Dante. There’s no self-doubt here, no endless rewriting of single sentences. To become an artist without a nattering critic in your head, the kind of weirdo who can be thrown from a horse-drawn carriage and then resume your narration without missing a beat, would be nothing short of a Christmas miracle for many a brilliant writer I know, established and emerging alike.

Though this was not the only miracle whose possibility I learned of from The Muppet Christmas Carol. Among the handful of things D.T. Max got right in his glowing encomium to the egodystonic writer David Foster Wallace is that every love story is a ghost story[3]. It’s a phrase I’ve always taken to be about the difficulties of desire: to want someone or something is to be desirous of that object at every point in time, as consumed by its past as its present and fearful of a future without it. And yet we are impermanent, just like the people we love: we are all always slowly turning into ghosts. Judging by titles like Frankenstein and Turn of the Screw, this was a fact known well by English writers in the 19th century. Dickens knew it, too, though A Christmas Carol doesn’t necessarily treat this impermanence as a bad thing.

As a kid, I was rarely moved by the Hallmark Christmas miracle. Oh, so the father was able to get that hard-to-get toy, and that made the divorced parents want to get back together? The bullies stopped picking on the nerdy kid at school, and he becomes the local hero? Some supernatural-but-still-notionally-secular deus ex machina occurs to make everyone realize that this holiday isn’t about what’s under your tree, but what’s in your heart? Okay, but then WHAT’S actually in our hearts? I wanted to ask. What’s that magic ingredient that makes one’s heart go from shriveled and black, the heart of a money- and love-hoarder, to healthy and red-blooded and generous? How exactly does one go about learning the meaning of Christmas?

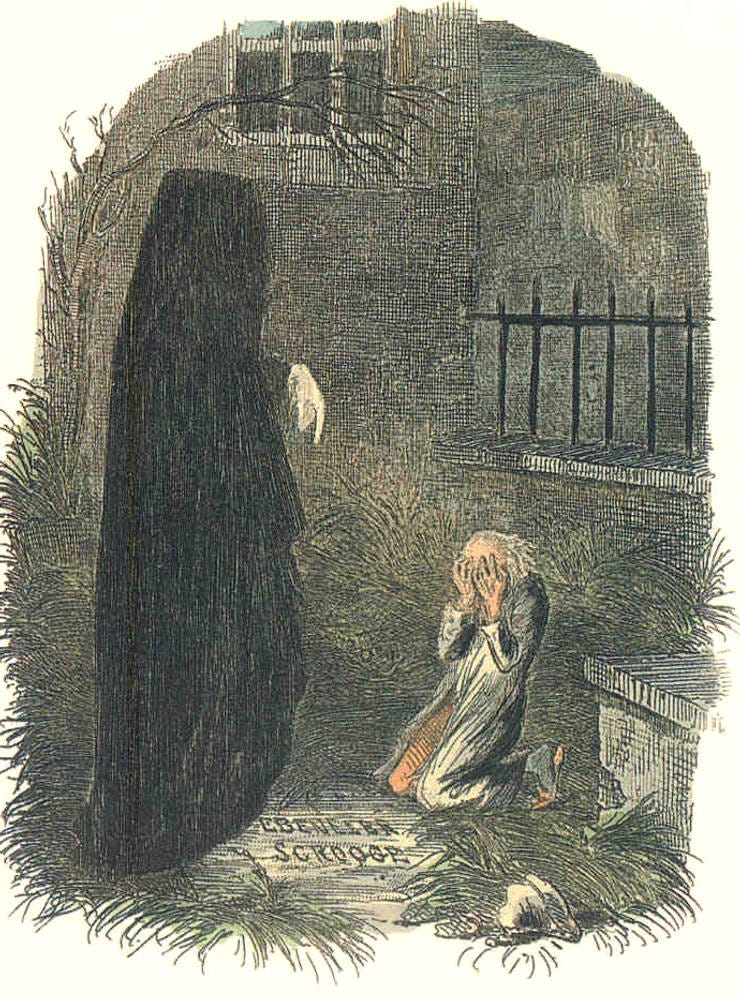

Happily, The Muppet Christmas Carol had an answer for me: By accepting the impermanence of all things. Through a series of spectral visitations, Scrooge learns that his money won’t follow him when he dies, but the facts of his life will. Rather than encourage him to hurriedly rebalance his life’s good deed/bad deed ledger – the Calvinist approach that would have been advocated by doctrinaire religious authorities and poor-wranglers like the instructors at London’s Field Lane Ragged School, to which Dickens once famously paid a visit – the spirits who visit Scrooge simply want him to focus on enjoyment of the present. Bound as we are in spacetime, incapable of changing the past or predicting the future, our approach to the present moment is really all we can control. And when Scrooge wakes up, it’s into a mercifully joyful present: a Christmas-present, where all planning for the future has been temporarily suspended in favor of braising gooses, singing carols and gathering around hearths. Heart open, Christmas goose in tow, Scrooge finds that his newfound warmth in the present outweighs the pettiness of his past. Even Miss Piggy is so swept up in the jollities of the day that she’s willing to forego her suspicions and break bread with him.

Christmas as we understand it in 2024 ought to be about embracing change and joy in one’s life. We could all use a little practice welcoming the possibility of change that doesn’t necessitate an increase in one’s possessions, a sculpting of one’s body, or another commonly-held sign of material prosperity. Too, we could all use some help understanding that one’s past can’t be overwritten or rewritten so much as it can be expanded upon, and that if we’re all going to become ghosts someday, then we might as well stop forestalling our joy.[4] Is it so radical to think that any of us at any point in time have exactly what we need to fuel more than just a fleeting moment of happiness? As someone who recently lost almost everything, you might be surprised to know that I don’t find this such a radical idea at all.

When you’re searching for the right Christmas movie to watch tonight, I hope you’ll consider The Muppet Christmas Carol. Beneath all the fur, feathers and puppet strings, those weird little creatures were showing us universal truths that we’ve all hoped – or maybe even known – to be true.

Welcome new subscribers, and thank you for reading! If you’re still looking for a last-minute holiday gift, consider gifting your loved one a year of the Cosmic Cheeto! And if you met me at The Big Gay Holiday Market last weekend and want to order another book of mine, drop me a line at frumkinr [at] gmail.com with your order and I’ll ship the requested books directly to you, free of charge :)

[1] The noun “gonzo” was apparently a Boston slang term meaning “last man standing after an all-night drinking marathon.” A disappointment – naming a literary subgenre after a Muppet would have been way better.

[2] Or beaked creatures of indeterminate species.

[3] The phrase itself is not Max’s, nor Wallace’s, but possibly Wallace’s teacher’s or the 20th century Australian writer Christina Stead’s.

[4] This is also the lesson of James Joyce’s “The Dead,” which is perhaps my favorite Christmas story of all time, but that’s a topic for a different essay.