I spent the better part of my twenties writing my debut novel, The Comedown, and by the time it hit shelves two years shy of my thirtieth birthday, decades of girlhood had prepared me to recognize the type of humiliation befalling me.

Perhaps you know what it’s like to spend hours in the mirror with a curling iron and Target lip gloss only to be overlooked by your crush at school? Or carefully constructing a treasure hunt for your friend’s birthday and then arriving at the park to learn that the treasure hunt has been scrapped because a more popular girl wants to get smoothies? Or deciding to try something new with a work friend or possible romantic partner only to be canceled on within minutes of your arrival? At best, you’re an afterthought. At worst, forgotten. Ignored.

To be clear, there’s nothing gendered about being ignored – men know this humiliation just as well as women, as do individuals of all flavors of self-determination (one might argue that having a write-in gender is either a precondition for feeling overlooked or a reaction to it). I’m just casting back to my girlhood because it’s what I know too well, it’s who I was and in many ways still am, and it’s rife with ready-to-hand similes:

Publishing a debut novel that gets ignored is like going to a school dance and being promptly abandoned by your date.

Publishing a debut novel that gets ignored is like thrilling when you learn you’ve been accepted to your dream college and then finding it filled with people smarter and more interesting than you.

Publishing a debut novel that gets ignored is like messaging several cute women on OK Cupid, watching as each leaves you on read, and then spotting one on a date with a guy who looks like Chris Pratt.

And so on.

Maybe you’re thinking, Hey, please chill out? You’re lucky to have published a debut novel at all, let alone one with a decent advance. And isn’t it super rare that a debut becomes a bestseller anyway? Also, did you say you wrote that thing in your early twenties? Maybe it’s okay that not everyone read it.

Reader, you’d be forgiven for thinking this way. Let me assure you that this is not an essay about how the first book I wrote was entitled to a massive reception and I to unqualified literary fame. Rather, it’s an essay about how dangerous it is to stake your entire sense of self-worth on a single thing of dubious outcome, and why it is that we writers love to do just that, again and again and again.

*

When I began writing the book that would become The Comedown, I felt, as many young adults do, that lots of things were going wrong in my life. I also felt that I didn’t have the time to fix them. Why waste valuable years “working on myself” – going to a twelve-step group, for instance, or journaling through my anxieties or figuring out how one cultivates abiding presence and self-love – when I could just aim for the silver bullet: writing a book so good that other people’s high opinions of it would somehow make me believe that I, too, was good? Surely such a bold plan had never failed anyone before, and wouldn’t fail me either.

Tender young fool that I was, I didn’t even have a chance to learn that “other people’s high opinions” of a book are quantified so variously as to be downright maddening. I could have gotten a rave reivew in the New York Times and ten minutes on Good Morning America and been a finalist for the National Book Award, but still managed to find “lapses” in other people’s high opinions when the book dropped off the bestseller list after four weeks, or got a bad review in the Washington Post, or wasn’t even longlisted for an award I felt sure I’d make the short list for. This is the dilemma of measuring one’s life by the markers of an art world both insular and ego-driven: you’ll arrive at the place where you told yourself you’d feel sufficiently bolstered by others’ approval, only to find there’s more approval to be sought. Much, much more.

The thing is, 99.99% of the world is external to oneself, meaning the approval to be sought is vast beyond belief. But how was I to know that? I got the New York Times rave – a shock and blessing, especially considering the deep admiration I’ll always have for the novels of the reviewer – and then: nothing. Or, next to nothing: four readings, one canceled because no one showed up. A handful of well-read friends and reviewers wrote about the book for smaller outlets, but the sales numbers remained so bad that my editor avoided sharing them with me. My agent at the time joked that more people had read the NYT review than the book itself, and pressured the publisher to make good on their promise of a small paperback run. No one bought the paperback, either.

Publishing a debut novel that gets ignored is like packing everything that feels special and important to you into 300-some pages and then staking the health of your career (and your mental wellbeing) on the chance that many strangers will find these same things just as special and important.

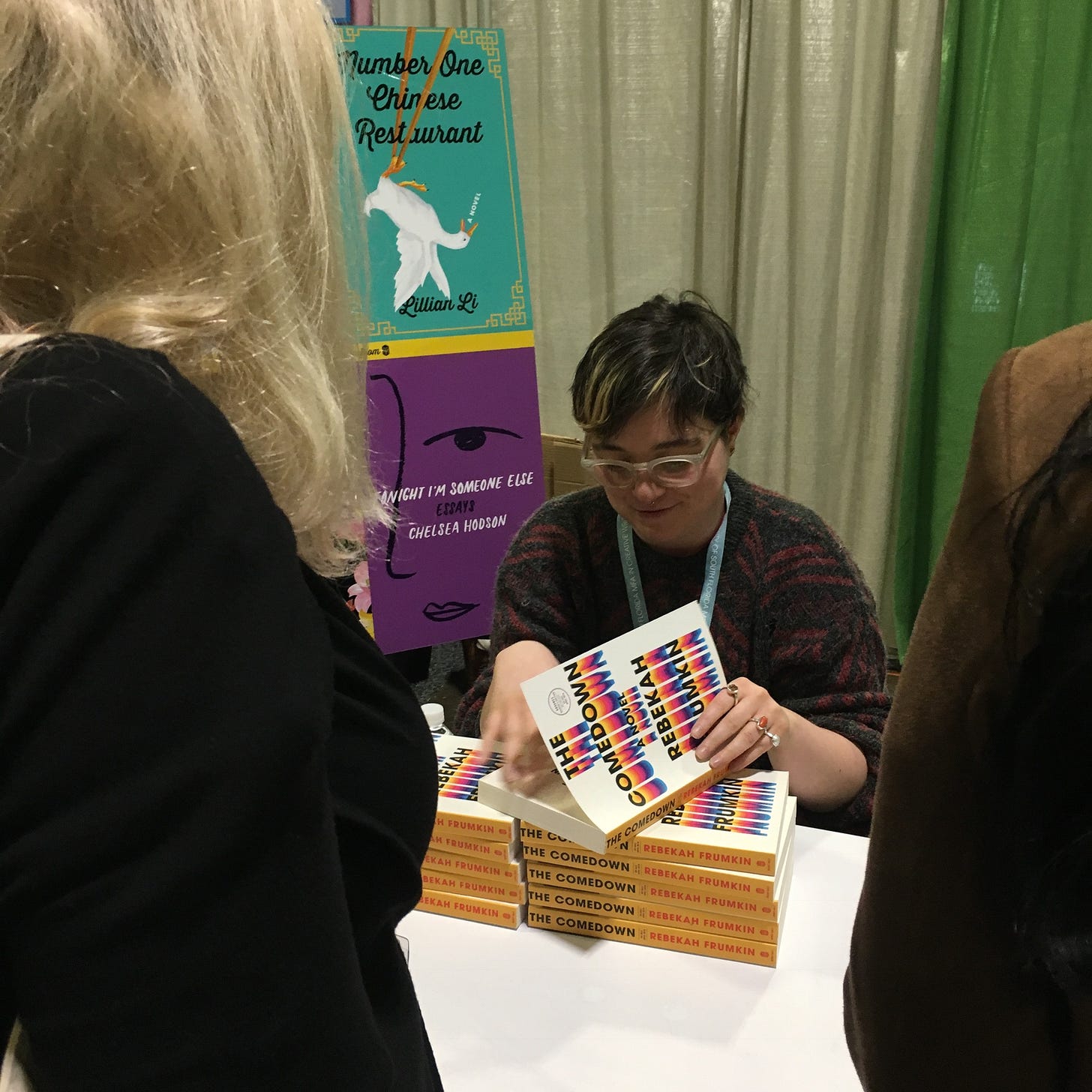

I went to the 2018 AWP in Tampa, where it was a rainy and cold March. Morosely, I signed a small stack of books. Morosely, I dosed myself with THC gummies and Xanax and wondered – often aloud, often at length, often to friends who would have rather been talking about anything else – where I’d gone wrong. Everyone told me that it was a crowded market, that life was long, that I could sell other books, that I ought to just keep writing. Regardless of my interlocutors’ kind intentions, I took all this to mean that though I had indeed failed, it was not too late to succeed, and that valuations of one’s art and self still had to be wrested from other people.

I changed my name and appearance before selling my next two books, and when I was spoken of by my agent or editors as “re-debuting,” I didn’t mind at all. In fact, I was often the one introducing the idea: what a great opportunity all my gender trouble presented to make a clean break from my embarrassing past. Let’s forget Rebekah Frumkin’s book ever happened and just go full steam ahead with Rafael’s.

But the thing about the past is that it won’t just lie down for a belly rub and call it a day. The past isn’t submissive, and if you try to send it away it just comes wandering back, sniffing around and pawing at your feet.

*

By the time The Comedown was briefly resurrected, I was well on my way to publishing my next two books and had begun to realize that the lifespan of a book, like that of a human, is long and winding and full of pleasant surprises. Such as finding new readers even after falling onto the backlist and out of print. Or realizing that a story’s value isn’t in how many people consume it, but that it gets told at all.

Kurt Vonnegut, himself a back-lister reinvented as a front-lister, once told recent graduates of the Iowa Writers Workshop that “one or two” of them could hope to meet with real success. Vonnegut’s concept of success, like my own in 2018, was at once too narrow and too broad: a self-sustaining writing career with enough notoriety to guarantee longevity. But what of the writer of the explosive bestseller who then struggles to write a follow-up? Or the writer with modest sales who’s equally fulfilled teaching creative writing independently or at a university? Or the writer who’s also an editor, a food critic, a backpacker, a trombonist, a parent, a cartoonist, an improv coach, a dog walker?

What about the writer who’s peeled herself away from the noise of other people’s opinions long enough to remember why she writes?

I can’t speak for you, but when I first sat down to a sheet of wide-ruled notebook paper as a kid, trusty Ticonderoga pencil in hand, it wasn’t because I hoped it would someday lead to a Whiting Award and an invitation to speak at Breadloaf. It was because writing was a joyful thing I couldn’t help but do. I had a story I was excited to tell, and the next logical step was to tell it.

We write our stories about superhero dogs and grandparents who turn into aliens only to realize that this writing thing is great, and that we’d like to keep doing it when we grow up. And then we grow up and get self-conscious and see all that’s involved in being a grown-up writer and get more self-conscious and either decide to continue with the process or not, often punishing ourselves for whatever decision we make (as grown-ups are wont).

We’ve all got to eat, I hear you thinking, and you’re right: for better or worse, one has to make a living in this world. And yet, aren’t there a whole lot of ways to do that? And yet, can’t the really successful writer be another person with a story she’s excited to tell, who knows the next logical step is to tell it?

I won’t pretend that writing a novel – or a memoir, a book of poetry, a collection of short stories or essays – isn’t an immensely personal thing, and that submitting what you’ve written for public consumption isn’t an act of extreme vulnerability. But I will also submit that you’re allowed to believe that the thing you’ve written is interesting and valuable by virtue of your own passion for it. This is true even before that thing is available to be judged, bought, and sold by the world at large.

It sounds counterintuitive, but I have now sat at enough folding tables featuring displays of my books to know that the more faith you have in yourself as an artist and the value of what you’re thinking and writing about, the easier it will be to talk about your books, the more people will stop to chat with you about them, the more copies you’ll sell. Conversely, the more you’re seeking your own value in the interest of those who wander by your table, the more fragile you’ll feel whenever it’s not apparent, the harder it will be to talk about your books, the fewer copies you’ll sell.

Call it spiritual economics, call it self-confidence, call it art for the artist. Whatever it’s called, I let “failure” turn me into a needy solipsist, so desperate for validation of my art that I was blinkered to the nuances of others’ lives and minds. Believe in your “failure” enough and you’ll become a black hole of need, driving not just friends and potential readers1 away but very real evidence of your own success as well. Indeed, I began to fetishize the story of my failure, to build whole elaborate, resentment-filled mythologies around it. I missed all the ways that my supposed embarrassment of a debut had picked itself up, dusted itself off, and was living its own life.

Nowadays, I’m proud of The Comedown. I’ve incorporated my stack of old hardbacks into my little library stocking project, and even signed some copies for favorite bookstores. I’ve learned that first books that don’t become runaway hits can still become incredible things: take Jonathan Lethem’s first book, Gun With Occasional Music, which was turned into a sculpture by the artist Robert The. Lethem writes of his book’s second use in The Ecstasy of Influence:

If the world can make room for both Lethem’s novel and Robert The’s sculpture, then it can certainly make room for more than one definition of what it means to lead a good and successful writing life. My definition: feeling a thrill whenever I begin a new project, wrestling with challenging ideas on the page, living dangerously in my novels so that I may live peacefully in my own life.

By this standard, reader, I’m the most successful writer I’ve ever been.

Or, as they’re sometimes known, future friends.

I often think about, amidst all the frustrations, how important it is to reach any student in a meaningful way. That small success is not really small, especially for those readers/students who are touched. Btw, I love your work but may have never encountered it if not for a reading at a very small community college! This is my way of saying “Please Come back! October?!!!

Before I read this article I need you to know that never would I describe or see you as “a failed novelist”