Calling My Parents: A Case Study

A series on familial estrangement and radical politics

This is part one of a three-part series. Read part two here.

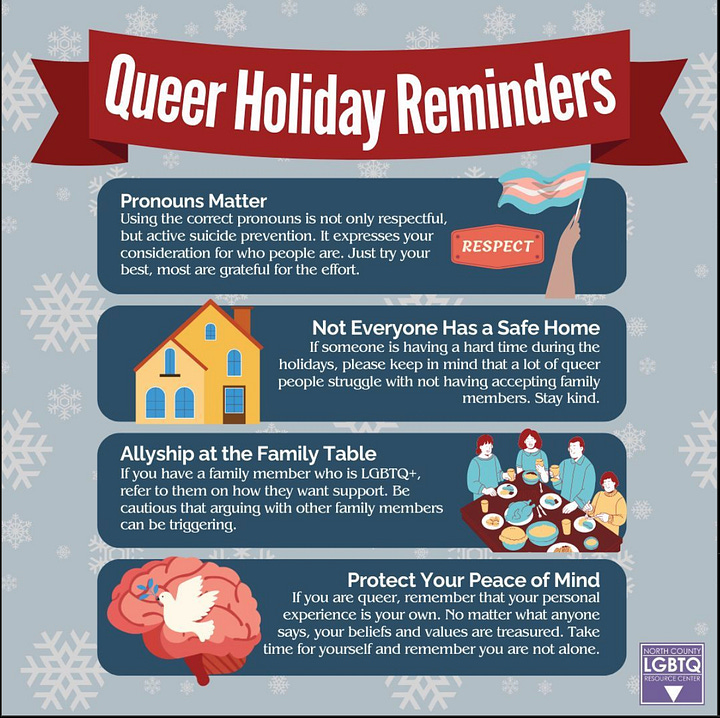

The holidays are upon us, reader – that time of year when various user algorithms would show me content about the supposed rift between me and my family. To all the queer people feeling alone this holiday season: WE SEE YOU, WE HEAR YOU, YOU ARE LOVED. I’d be given 10 Easy Tips for Throwing the Perfect Queer Friendsgiving. I’d be coached on how to “hold and care for” my inner child as I navigated another holiday season without my parents. In the event that social media assumed I was in contact with my family, they’d offer me advice on how to draw strict boundaries with them: No chit-chat. Hold your ground. Politics ARE personal, regardless of what they say. Love is love, except when the people you love refuse to acknowledge your basic humanity.

The algorithms had me all wrong. Or mostly wrong. Back when I was still on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter – I left them all in early 2024 for a variety of reasons[1] — I was indeed in contact with my family, but things were not rosy. Our relationship was fracturing in bizarre ways, an outcome none of us could have anticipated, and one I was ashamed and angry about. My parents kept reaching out, but our conversations would dissolve into the screaming fits and sternly issued warnings of my adolescence. Had our communication always been this contentious? Were they embarrassed of me? Judging me? Social media kept reminding me that I, an enlightened critic of power, should be the one judging them.

I’m an only child, and I had an idyllic middle class childhood: dance classes, art classes, daily access to nature, enthusiastic parental love and support. They genuinely believed I could grow up to do whatever I wanted to, including make art for a living. So I told them everything about my life. Here was a short story I was writing about dogs and cats who were best friends. Here was this problem I was having at school, or all the lyrics to my favorite song from my favorite Disney channel original movie[2]. My parents were my advocates, and I was theirs. They thought I deserved the best, and I thought they did, too. Their world was my world, and their decisions were beyond reproach.

But family is a messy and unpredictable human enterprise, so messy and unpredictable things befell my cozy family unit. In college I started to binge drink and smoke a lot of cannabis, and my exuberant self-disclosure turned into a weird kind of self-surveillance. Each wretched-up bag of Franzia or brain-ripping bong hit felt like a betrayal of my parents, so I obsessively reported every sober detail of my academic life in hopes they’d see how “well” I was doing. They were worried – what good parents don’t worry about their child? – and sought to quell that worry with intervention. Calls, texts, emails, endless suggestions about what I ought to do. It was overwhelming. We were all just trying our best.

I graduated college and realized I was bisexual. Then I was in a lesbian relationship. It wasn’t so much my non-normative sexuality my parents seemed to fear as how much my life began to differ from their own, or at the very least from the life I’d been on track to have. As a kid, I’d had crushes on boys, wore my hair long, and exhibited the kind of work ethic necessary to replicate my social class. By my mid 20s, the work ethic hadn’t gone away, but certain tethers to normalcy had. I dated women, dyed my hair pink, and smoked DMT along with my weed – mine was a bohemian life edged with self-destruction.

Yet even without the self-destruction, I still would have been different. I was determined to have a career as a writer – the only one so reckless in a family of accountants, attorneys and healthcare professionals. I also genuinely believed (and still do) in creative community, reciprocity, and generosity – all things fairly impossible to come by in the socially conservative suburb where I grew up. I chafed against the high school where I was the frequent target of determined bullies. I sought an escape in college, where I fit in well on an insulated liberal arts campus. I found some community (which I still treasure to this day) and also a set of material standards to aspire to: go to a name-brand grad school, get a well-salaried job, establish a well-financed household.

Of course, these weren’t the only standards to be met. My friends and I had stringent political standards, too. I needed to constantly acknowledge my privilege lest I come across like some bigot reveling in her well-resourced whiteness; I needed to defer to those more marginalized than me and make white men defer to me in turn; I needed to enjoy nothing, for ours was a fundamentally unjust world and the Work Was Never To Be Done.

It was a weird kind of paradox, this idea that I needed to succeed by normative, capitalist standards while engaging in their critique. But I took to it happily. It offered me precisely the combination of prestige-seeking and self-abnegation that I liked best, a neat blend of the pieties of my parents’ middle-class world (which I still sought approval from) and an intellectual framework to lambast them. I was not the weird loser my high school bullies claimed I was, but the morally righteous victim of an oppressive cisheteropatriarchal social structure. Though I had suffered, it was because I was the more authentic one, the braver one, and my illustrious career would be built on demonstrating just how true this had been all along. The world could thank me for it later.

To be clear, progressive critiques of power remain valuable to me and the work that I do. They name bona fide social inequalities that both persist from and perpetuate human rights violations. Racial inequality and racially motivated violence are gruesome tears in the social fabric of the United States; so are sex-based inequality and the prevalence of sexual assault. Class stratification keeps large groups of people locked away from each other and dangerously under-resourced. Indeed, people frequently harm each other, and whole categories of people are harmed and exploited on the basis of identity. It’s not these facts themselves that fractured my relationship with my family, but their misapplication.

In my late 20s, I landed an academic job. Higher ed was the perfect place to take potshots at hegemony while maintaining financial stability. If my critical theory potshots were smart enough and I was truly willing to grind, stability could even turn into something resembling affluence. Hired into an old guard English department at a small-town university, I was more socially isolated than I’d ever been in my life. When COVID hit, things just got worse. Teaching online only intensified my anxieties about my toxic and paranoid work environment; I could think of many reasons why the power-wielders in my department were haranguing me, and they all had to do with my identity. My parents kept intervening, plying me with try-hard solutions to what felt like the intractable problems of my workplace. I tried being quieter, taking on more work, positioning myself as an easygoing team player. All of it backfired disastrously.

So I did what I knew how to do, and identified all the ways this was the problem of patriarchal bad actors, high school bullies with English PhDs. My parents did what they knew how to do and tried very hard to get me to fit myself into the job – “professor” is a more brag-worthy title for one’s kid than “aimless drifter” or “psychonaut lesbian,” after all. In truth, the work environment was quite bad, but that didn’t mean I was some Noble Blameless Victim, nor that I was a colossal screwup destined for a life of instability. My parents were afraid, and I was exhausted. Once again, we were all just trying our best.

But our best was no match for what was to come. By 2023, I was two years into my transition. Much of what I said and believed – about my pronouns, my deadname, my dysphoria – was totally incomprehensible to my parents, and by then this struck me as no surprise. They had so far been misguided in attempting to fit me into a box of suburban respectability, a place where I would always be regarded as weird and ill-fitting anyway. As we suffered through contentious phone call after contentious phone call, I couldn’t help wondering if maybe all that social media content was right. Was I yet another emotionally adrift queer adult horribly misunderstood by transphobic parents? Was this schism revealing tensions that had always been percolating between us? Worse yet: was this all an indicator of some hidden, deeper harm?

I know the fear my parents experienced during this time because they’ve told me about it. I was self-destructing again, and at a time in life when my peers were having children and buying houses. I can also guess how exasperated my parents felt, not just by our troubled conversations but by my increasingly obtuse life choices. We were different from each other, certainly, but we were pouring all our energies into correcting those differences instead of understanding them. Contact began to feel impossible. What sort of liberation praxis involves the oppressed regularly phoning up the oppressor? Feeling fed up makes it harder and harder to try one’s best. This, too, was echoed by the queer content I was regularly consuming online.

I have friends whose parents have actually extorted, threatened and stalked them. We’re talking parents who’ve cooked or dealt drugs, who’ve kicked their underage children out of the house, who were genuinely too paranoid or self-involved to bother with their children’s wellbeing. Parents who, upon learning that their kid was gay or voting for a different candidate or dating someone of a different race or socioeconomic class, promptly informed them that they were no longer related. My own relationship with my parents couldn’t have been more different, but the algorithm didn’t want me to think that way. As far as my social media scrolls were concerned, I was oppressed, alone and dangerously misunderstood.

Luckily, the algorithm would always be there to pick up the pieces for me. It knew me so well! I was a Saggitarian transmasc liberation-seeker. An anarcho-syndicalist ENFP sapphic. AFAB and neurodivergent with an enneagram of 7, a woke AF theory spoonie, a wonkish millennial he/they. The algorithm had just the influencer for me, precisely the product. Would I mind following this brand and liking five of their posts for a chance to win an all-trans pool party? Did I know that this mayoral candidate was a shithead, but this one was daddy? Was I boycotting X fast food chain for Y geopolitical reason, or was I part of the problem? I clicked and swiped and faved and retweeted. I retreated deeper into a world that bore no resemblance to the one I’d grown up in, which I began to understand as a site of pure suffocation and betrayal. I needed to radicalize. I needed to glow up. I could start by ridding my life of hegemonic harm.

My parents are baby boomers. They were a bit too young in 1969 to travel to a certain farm[3] for a certain concert, but not so young that they couldn’t memorize the famous set list. I was twelve when they introduced me to the music of Neil Young. By fourteen, I had a favorite album – Harvest – and by sixteen, I had burned a master CD of all my favorite Neil Young songs. “Heart of Gold” was top of the list, followed by “Ohio” – so captivating and atmospheric that I would later set a portion of my first novel during the Kent State shooting – and “Old Man.” In that song, Neil Young is speaking to the generations above his own, ex-GIs and housewives completely bewildered by the consciousness-raising civil rights movement of the 60s and 70s.

The song could have been an angry screed about the stubborn resistance of older generations to the world-changing politics of youth. It could have been a call to burn it all down, including the family unit itself. Instead, Neil Young identifies with the old man he’s singing to:

Old man, take a look at my life, I’m a lot like you

I need someone to love me the whole day through

Ah, one look in my eyes and you can tell that’s true

On the boom box in my room, I played that song over and over and over again.

Each generation thinks it’s the first to shrug off the past and remake the present; each generation is blinkered to the efforts of the ones before it. Consider this, reader: that old person messing up your pronouns was once a young person fighting with their parents over boycotting the segregated lunch counter. He or she was once going to protests like you are, feeling misunderstood like you are, and seeking like-minded chosen family just like you are.

And believe me, if you were a baby boomer who wanted to tune in, turn on, and drop out of your parents’ straitlaced world, the 70s boasted a range of families to choose from. There was the Manson Family, for instance, or Rev. Jim Jones’s super egalitarian People’s Temple, or Yogi Bhajan’s Healthy, Happy, Holy “Sikhism.” These families were there to affirm you – you’d always been right about being different and hipper and more enlightened than the squares around you – and help you draw some much-needed boundaries. Move to our commune, stop speaking to your friends, cut off your parents. Those people hurt you; they don’t get you. We’re your family now.

This sinister form of chosen family hasn’t gone away. It’s just mutated into strange new shapes. There was the pseudoscientific practice of “recovered memories” in the 80s and 90s, for instance – otherwise known as manipulating the vulnerable with the power of suggestion – as well as millennial “spiritual gurus” like Teal Swan, who makes use of this decades-old behavioral con to groom and isolate her followers. You won’t become any more healed or enlightened by “realizing” your loved ones abused you and cutting off your parents to live on Teal Swan’s compound. What you will become is more afraid, devoid of a support network, and wholly dependent on one person who claims to have all the answers you need.

Most of us have unresolved dysfunction in our families. In some cases, that dysfunction is so profound that it really does necessitate estrangement. In many cases – including my own – it more closely resembles growing pains: the family is changing over time, and adapting to those changes necessitates a full-scale effort. Here’s the thing: the renewed closeness and understanding are well worth the effort.

Most of us will make friends in this life so close that we count them as family. In some cases, those friends will actually supplant family, offering us all the emotional heavy lifting and unconditional love that entails. In many cases – including my own – those friends will coexist with our families, expanding an already robust support network. In such a blended family, the chosen members don’t need to exclude the biological ones, nor vice versa.

The growing rift between me and my family has long since been repaired, much to everyone’s relief. You might be wondering how that happened, and why various user algorithms were so hell-bent on convincing me it never could. I’ll be tackling those topics in the next two essays in this series, both of which will be available in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, I hope you’ll enjoy this 1971 performance of “Old Man,” reader. He’s a lot like you:

This essay is part one in a series. Subsequent installments below:

[1] Brutal user addiction and contact from stalkers were the darkest among them.

[2] The Cheetah Girls is unmatched. Except maybe by The Cheetah Girls 2.

[3] But Max Yasgur was a Frumkin family friend – true story!!

This line stood out to me: "We were different from each other, certainly, but we were pouring all our energies into correcting those differences instead of understanding them."

What a profoundly moving, brilliantly written, thoughtful piece. Deeply grateful you’ve shared this with us and I look forward to reading more!