On transness, desire, and getting what we want

Demystification of queer theory & some gender metaphysics & a wedding

What does gender have to do with desire? What does transness have to do with getting what one wants?

Nowadays I get asked a lot of questions, reader. And I don’t mean the pointed Are you a boy or a girl? sort of questions posed by curious kids as I stroll in my weird little shoes down the weird little street. I’m talking questions from concerned friends who inquire after my gender as though it were an ailing relative in a house full of black mold. “What are your, um, pronouns Raf?” they ask. “How’s the discourse?”

“Oh, it’s very bad!” I say, though I say it with a smile, which throws them. “But I, personally, am pretty good. And my pronouns are all doing quite well, thank you!” Then I pull the accordion of photos out of my wallet: my pronouns’ yearbook portraits, birthday pictures, and a group photo of the entire family on a recent fly-fishing trip. Little she/her caught a giant angler, which made he/they, who’d only caught a rainbow trout, burst into tears on the spot.

But really, I understand why these friends are asking. Upon reading my Bobby Flay humor piece – intended to satirize how odd it’s felt to reject my assigned sex, which seemed impossible to “correctly” inhabit, only to feel pressured into “correctly” inhabiting a different one – a close friend of mine asked for some clarification on the “born this way” argument as it relates to transness. He texted me: I’ve heard “trans men are men” and “trans women are women,” but to be honest I’ve only heard “they want to be men or women, but aren’t” coming from folks who genuinely seem to want to harm queer people. Is this issue something the trans community is divided on, or is there more I should know?

And that was when I realized I had to admit what I’d become: a Gay-Ass Wonk for Theory (GAWT). I thanked my dear friend for his valuable question and apologized for being so deep in the weeds that I wasn’t doing my part to clarify widespread matters of confusion. As we gear up for an election whose outcome will be determined by America’s collective understanding of the mind-body problem, I would love to share with you a slightly expanded version of the answer I gave my friend.

*

Was I born this way?

One hot topic among us GAWTs is what I’ll call the “dialectics of desire.” Though we can recognize the immense political utility of statements such as “born this way” and “gay is not a choice” from the successful campaign for marriage equality back in 2015, we’re not altogether sure that who we are and what we want are totally inextricable, nor that the social and political environments we find ourselves in don’t also play a role in shaping those things. We are always negotiating what we want with an external world that wants things from us, how we see ourselves with how we’re seen (and furthermore, how we want to be seen). All this is not to mention the fact that the discourses of identity and biological determinism have historically made unpleasant bedfellows.

It's a tricky dance, to be sure, and it’s why Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity has become such a prominent part of our cultural fabric. Butler noted the interplay of appearance and desire, the contingency of the social, and the power of the speech act in creating one’s gendered presentation. In addition to gender being a “corporeal style,” Butler says it’s also about what you say and how you say it.

Which begs an interesting question: can saying “I am a man” have the same power-to-make-real as saying “I promise”? When you say I promise, you are actually doing the promising. So does the same go for an assertion of one’s gender identity? Do I become a man simply by stating as much, by living out the “script” of manhood?

It's certainly presented me a lot to chew on. If anything, Butler’s theory has opened many eyes to the idea of gender’s contingency. Meaning humans “perform” maleness or femaleness in different ways depending on a variety of factors including: pre-established norms, social milieu, desire, and proclivity to subversion of all of the above. This means, of course, that choice can come into play when it comes to gender, though that doesn’t mean that it’s the only factor in play.

I disagree with trans critic and theorist Andrea Long Chu on quite a lot of things, but there are some key points we do see eye-to-eye on. In “On Liking Women,” the n+1 essay that launched her career, she makes a Butler-adjacent argument for transition less as the external confirmation of an innate gender identity than as the realization of desire:

I doubt that any of us transition simply because we want to “be” women, in some abstract, academic way. I certainly didn’t. I transitioned for gossip and compliments, lipstick and mascara, for crying at the movies, for being someone’s girlfriend, for letting her pay the check or carry my bags, for the benevolent chauvinism of bank tellers and cable guys, for the telephonic intimacy of long-distance female friendship, for fixing my makeup in the bathroom flanked like Christ by a sinner on each side, for sex toys, for feeling hot, for getting hit on by butches, for that secret knowledge of which dykes to watch out for, for Daisy Dukes, bikini tops, and all the dresses, and, my god, for the breasts. But now you begin to see the problem with desire: we rarely want the things we should.

Chu acknowledges that these are the traditional trappings of patriarchal femininity – culturally-mediated and performed. “Perhaps my consciousness needs raising,” she writes. “I muster a shrug.”

It’s a fair point, I think. What is it to be a woman or man in the absence of any sort of social or cultural framework in which those concepts are given meaning? Must we first establish a category in order to occupy it? Or, after Butler, at the very least announce our intent to occupy a category in such-and-such a way?

In “On Liking Women Too Much,” an essay about my own transition that I’m working on for The Point, I offer my own thoughts on this topic:

What I’ve found is not only what I was running from (persistent and pervasive shame, the feeling of having failed in my gender, male scrutiny) and what I was running to (the idealized ease of manhood, fantasies of freedom and autonomy I’d cultivated since childhood, the chance not just to have a wife but to look like someone who has a wife), but also a belief in the post-feminine: the idea that I could be born with a female biology and yet still transcend its hated rhythms and mores, the outrageous and ungovernable set of disciplines exacted against my female body by the world through which it was destined to move.

Like Chu, I wasn’t seeking some kind of academic-Platonic manhood untouched by cultural baggage. She sought Daisy Dukes, bikini tops, and benevolent chauvinism; I sought being looked in the eye instead of spoken over, becoming invisible to the straight male gaze, and getting to be considered my own life’s protagonist. Could you blame either of us, knowing what we’d come from? And furthermore – what would that academic-Platonic-gnostic man- or woman-concept even look like? And how would one even go about confirming said concept?

*

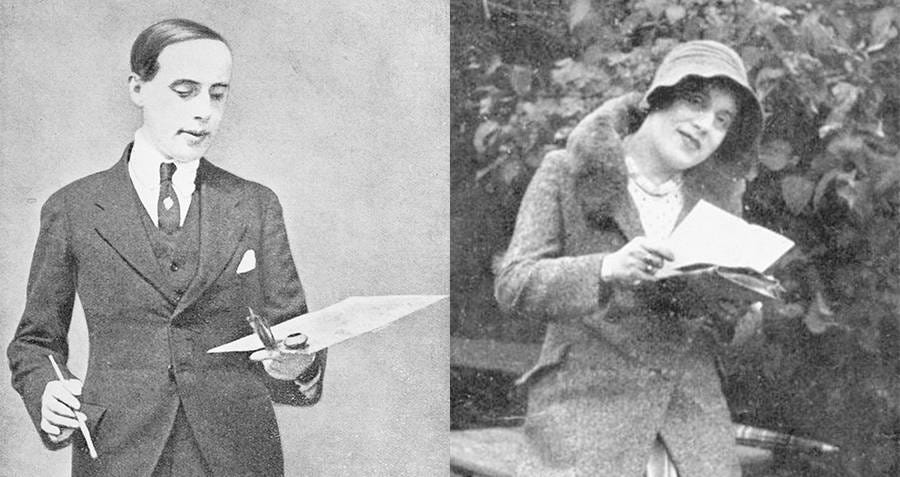

Medical Consumerism, or: The Danish Boy

Okay, you got me, subscriber: I think self-determination is great! When an adult capable of reason and consent makes a choice, and the outcome of said choice does nothing to imperil the greater good, I think the adult’s right to make said choice should be enshrined. It would be a human rights issue if, say, the Ministry of Truth were to intervene on “behalf” of said adult, to inform them that, whoops, it’s actually Big Brother who knows best when it comes matters of their mind and body!

No, this GAWT has absolutely no objection to people making choices about their bodies. I’m quite sure my legislated-over uterus would agree: how we mediate the ongoing struggle of our embodiment is a question for philosophy and science and spiritualism but certainly not for congress. It’s also something that we might consider handling on an individual basis. For instance: how Marina Abramovic has chosen to take her body to extremes for her art is a choice that I, a great fan of her work, am grateful she was allowed to make. Likewise Johnny Knoxville, whose near-deadly stunts on Jackass, a friend of mine recently pointed out, have done as much to clarify the lived experience of manhood as Abramovic’s performance pieces have for womanhood.

What I take issue with when it comes to self-determination via gender-affirming medicine is not those seeking the medicine, but the failures of the medicine itself. Namely, trans medicine’s frequently benighted quest to realize that impossible academic-Platonic-gnostic gender archetype. Recall a few paragraphs above, how not even us gender-expanders had such a concept in mind when we decided to transition? Then perhaps you’ll be shocked — or depressingly unshocked — to hear that doctors do.

There are the plastic surgeons who want you to lose weight before any of a number of gender-affirming surgeries. Perhaps that’s just for safety reasons? you ask hopefully, to which I can only respond with my own lived experience: a chauvinist surgeon who described me as “overweight” when I weighed far less than I do now and was well within his BMI range for surgery, painfully manhandled my breasts in the exam room pre-surgery, told me to “leave it to him” about the spacing of my nipples and then barked at me when I asked if I’d ever recover sensation in them. (“They were sitting in the tray for two hours while you were on the table, so of course not!”) And that guy was supposedly top-of-the-line: don’t even get me started on my partner’s surgeon, who accepted state insurance.

And then there was the trans FOLX doctor who Zoomed with me for all of twenty minutes and, when I expressed some hesitation about starting testosterone, said: “Well you’ve gotten the top surgery and usually most guys are on T before they get the surgery so you’ve already made the big step.” I signed up for the prescription but was so rattled by the consultation that I didn’t take my first injection until months later.

Here's what doesn’t feel weird or hard to understand: being discontented with the rigid gender expectations you’ve been born into. Also, being predisposed to gender exploration and expansion. If we’re going to join Jack Halberstam in taking “trans” to mean something like a poststructuralist defiance of the classification of established norms and identities that embraces all forms of variance,1 then it would be pretty difficult to argue that this phenomenon of feeling out of step with the world in one’s own skin, this desire to go against a normative grain, is not a supremely human one.

However we choose to reconcile our feelings of unease is, of course, our business. I, Chu, and a whole host of others have sought the services of gender-affirming medicine. There’s nothing wrong with our having chosen that, but it’s certainly frustrating to have had to contend with medical hubris in the process. It’s frustrating that we, the gender-distressed in the late capitalist West, are offered yet another consumerist model as the primary means of easing that distress. It’s frustrating that said model has placed us on what feels like a hasty and impersonal assembly line of HRT and FFS and masculinized or feminized chests and vaginoplasties and phalloplasties, undertaken by doctors whose residencies in endocrinology and plastic surgery miraculously gave them what not even Plato had: an innate understanding of the metaphysical categories of “woman” and “man,” and knowledge of exactly what ought to be done to achieve membership in either of those categories.

Ask anyone who’s undergone medical transition and I wager they’ll have a story or two to tell you about how their doctors’ “visions” for their bodies were at odds with their own. All of us who’ve made the rounds in the body positivity movement (or have spent any time conversing with its nerdy GAWT cousin, biopolitics) know that Western medicine’s gambit has always been to set its consumers down a certain path of becoming. In measuring our BMI, prescribing us our psych meds and our weight-management drugs, making its official recommendations about what to eat and what gene therapies to get and how to conceive (or whether we should conceive), medicine is nudging us towards health. And all too often, “health” most closely resembles the physiological condition of being thin, white, affluent, able-bodied and gender-conforming.

Perhaps this was partly why, after her vaginoplasty in 1930, Lili Elbe and her surgeon were reported to have been amazed at the newly feminine script of her handwriting, as well as by the girlish timber of her voice. Of course these would both have been unaffected by the surgery and hormone treatments, notes trans media theorist Sandy Stone. Instead, Stone says, there had been “barriers built within a single subject” by Elbe’s surgeon:

Lili displaces the irruptive masculine self, still dangerously present within her, onto the God-figure of her surgeon and therapist Werner Kreutz, whom she calls The Professor of The Miracle Man. The professor is He Who Molds and Lili is that which is molded. What The Professor is now doing with Lili is nothing less than an emotional molding, which is preceding the physical molding into a woman.

You’d think we would have made some progress with medical hubris since 1930 – and I’m certainly not ruling out the existence of compassionate doctors in every field – but I’ve found that the gender physician who’d rather you shut up and take their advice while they do their molding is far more common than not, especially in the field of plastic surgery. And here we have a weird horseshoe, friends: in choosing self-determination via the medical consumerist model, I find myself all too often in a situation where my self-knowledge – and thus autonomy – is less than respected. It’s been degraded, even.

This is where I think the self-determinative thread can get lost with medical transition, where I was made to feel like the Dutch Boy after Lili Elbe’s Dutch Girl: that sticky old dialectics of desire that I mentioned all those paragraphs ago. If transition can be motivated by desire and desire can be informed by sociocultural factors, then are we not sometimes transitioning into an idea of who we ought to be as opposed to reifying who we are or want to be? And furthermore, what’s keeping our doctors from having their opinions of who we ought to be? What’s keeping them from forging us in the smithies of their ORs, precisely as they see fit? They are the ones capable of working miracles, after all.

All too often, we mistake a critique of the systems designed to help us realize our “authentic selves” as dismissals of the very individuals seeking relief from those systems. It’s a real bummer to see the trans subject and the gender doctor merge in the discourse: we’re about as different as Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins in Pygmalion!

What ought to be at stake here is not the right of the distressed subject to realize themselves – to become who they’d like to be, or to confirm who they are – but the medical licenses and endowed chairs of the physicians and professors whose ideas of said becoming run afoul of the respectful treatment of their clients. And, GAWT that I am, I want to talk more about the dialectics of desire – not just in classrooms or in doctor’s offices but in the book clubs and support groups and various online spaces that constitute the postmodern queer agora. Surely we’ve progressed beyond Tumblr’s Genderbread Person by now?2 Surely none of us need to be queer theorists or self-proclaimed public intellectuals to be candid about what we want, and how that has or hasn’t been informed by what people want from us? The more honest we are about our own mental waters, the less murky they become, and the more confidently we’ll be able to proceed down the path to self-determination. Which, of course, makes it less likely for our journey to get hijacked by someone who’d rather “mold” us than listen to us, all while billing our insurance for $40,000.

*

What’s a GAWT to do?

One answer to this question might be: make it easier for folks outside the trans experience to understand what’s happening on the inside. Another might be: continue living as I am. And yet another, which seems to follow logically from the first two: be as honest as possible about the phenomenology of transition. Like any human experience, it’s been a fascinating mixed bag. But what it certainly hasn’t been is the silver bullet that cured all my problems and perfectly righted my life’s nosedive.

Let me be painstakingly clear here: gender transition worked for me, but not in the way it’s supposed to. As in, I haven’t felt any more a man than I did a woman, but what I did feel for the first time ever was the ability to explore my femininity from the safe vantage point of my adopted masculinity. At first, it was a therapeutic opportunity to disavow a performance of womanhood that I’d been cowed into, and that had never felt like my own. I wrote about it in “The Artist Is Banned for Violating Community Guidelines,” an essay for Lit Hub on transness, feminism and how the subversive antics of e-girl content creator Belle Delphine remind me of the performance art of Marina Abramovic:

Having been on both sides of the coin here – born a girl expected to wear makeup, flatter men, and maintain an “acceptable” weight and then transitioning into a Big Lebowski-meets-Birdcage weirdo whose chaotic buffoonery isn’t just tolerated, but celebrated – my interest in Delphine-as-artist has only intensified. Appearance-wise, I am farther now than I have ever been from whatever “feminine ideal” her gamer dude fans imagine she embodies, but watching her videos makes me feel closer than ever to my own experience of femininity – which is to say, womanhood-as-performance, or womanhood-as-irony. Heterosexual courtship less a genuinely pleasurable activity than something to be likened to caring for a dead pet squid. My own “prettiness” less something deeply felt than an elaborate “girl” cosplay: my eyelashes, cleavage, and desire for men all laughably fake. And this is how Delphine manages to thematize the strange quagmires of both womanhood and transness at once.

And then it became less about disavowing the aspects of womanhood that had felt like drag and more about discovering those I did identify with. I wrote about that experience in this essay on being a transmasculine Swiftie:

If Tortured Poets Department had come out during the height of my self-torture due to internalized misogyny (roughly ages 16-22), I would have been quick to join the chorus of Swift-hatred. I would have gleefully picked apart her lyrics, or gestured to the DAUMD as conclusive demonstration of how one cannot be both boy-crazy and a serious artist, and probably raised my eyebrows at avowed Swifties as many have recently raised their eyebrows at me. Anything to separate myself from that pathetic, cloying, sparkly pink mass of girliness: anything to show that I was not like the other girls, that I was smart and serious and funny just like the guys. If only I could tell that girl that she would someday be accepted as one of the guys, would be allowed into that coveted inner sanctum of rarefied tastes and fancy wristwatches and unabashed mansplaining, and would end up preferring the ethos of the sparkly pink mass instead.

And this was how, slowly but surely, “becoming” a man jump-started a process of healing some major self-loathing – a process that would ultimately lead to me integrating my masculinity and femininity, to feeling just as comfortable with the label “trans man” as with the label “gender-nonconforming woman” (or my own very GAWT label: “testoform butch lesbian”). If sex and gender are distinct, as Butler says, then I can perform the latter socially while being inscribed with the former genetically. So rather than erase Rebekah with Rafael, I can simply recognize him as another step in her lifelong process of becoming: a process to which, delightfully, there need be no rigidly determined end.

When my wife and I got married last month and the judge asked her if she’d take me – this man – to be her lawfully wedded husband, we were both too busy staring into each other’s eyes and smile-laughing and crying tears of joy to think about all the activism and debate – political, metaphysical – that had gone into making it possible for us to stand in that courthouse together. She looked like the cottagecore beauty that she is, and I looked like if Tony Stark had gotten several humanities degrees, and both our social security cards read SEX: F, though my driver’s license read SEX: M. Did it matter that we’d been “born this way” or molded by the world we were born into? Did it matter that I looked like Professor Iron Man as a confirmation of an innate gender identity or a realization of socially contingent desires?

“Survival is not a theory,” said Black lesbian philosopher and feminist Audre Lorde. “It’s a matter of everyday living and making decisions.” It’s a true statement in my experience, in need of only one addendum: love isn’t a theory, either.

*

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this essay, I hope you’ll consider supporting The Cosmic Cheeto in one of these ways:

Become a free subscriber and recommend this newsletter to others who may be interested!

If you’re already a free subscriber, consider upgrading to $5 monthly or $50 yearly: paid subscribers help fund the work I do here, and will soon be able to access exclusive, paid-only content!

If you don’t want to make the commitment to becoming a paid subscriber but still found this essay interesting or educational, consider leaving me a tip on Venmo! Thank you :)

Jack Halberstam is a queer theorist and gender abolitionist who sees failure to conform to the expectations of heteropatriarchy as a positive avenue to queer futurity.

I really appreciate Rowan Wilson’s candor about his transition in this essay, which ventures beyond the tired, over-politicized sanctimony of Innate Gender Identity and into the realm of psychology and desire — specifically his fascinations with effete knights and Niles Crane.