A Woman in a Girl's Body

A healthcare professional on her Turner Syndrome and what we talk about when we talk about intersex

Our futures are not spelled out by our chromosomes, subscriber — at least not entirely. It’s a truth universally acknowledged (within Western liberal society) that fate is the thing we question and refine in order to produce our future, that desire and determinism make uneasy bedfellows. “Born this way” may have worked as a rhetorical strategy to win us marriage equality, but start talk of a “gay gene” and faces will blanch1.

Becoming the captain of one’s own ship — whether that “ship” be your career, your mind, or your body — seems like the good and logical outcome of centuries of Enlightenment rationalism. But it can also make us vulnerable to some strange postures of denial. It seems uncontroversial that we ought to have a right to choose, but when can those choices override material reality? I’ve explored this topic as it relates to my own experiences of sex and gender in this very Substack — from the medical consumerism of “born in the wrong body” to gender as something one can “fail” at.

Then I began reading my friend Claire's essays, and I was gripped: here was a fascinating take on these topics from a refreshing new perspective. Over at Irreplicable, Claire — a midwife and reproductive health clinician who has Turner Syndrome — is writing about starting a family via egg donation and surrogacy in a way that thoughtfully explores genetics, womanhood as a social role, and the meaning of “intersex.” Claire’s story not only challenges commonly held beliefs about intersex, but asks us to expand our thinking on a variety of topics: Can hormone replacement therapy be understood as something that reifies biological sex as opposed to overwriting it? Can the right to reproduce be something a heterosexual couple might have to advocate for, albeit differently from their same-sex counterparts?

Naturally, I had to pitch Claire on writing a guest post for the Cosmic Cheeto. She kindly agreed. In the powerful essay below, Claire writes with great insight and candor about intersex, HRT as an entrée into adulthood, and becoming a parent in the gayest of ways.

Enjoy the read, and subscribe to Irreplicable for more!

**This is the first in a series of guest essays I hope to publish about an array of current “hot button” topics including gender, academia, cults, medicine, technology and ideological captivity in the digital age. I aim to showcase a diversity of voices; the views expressed in these essays are those of the writers and may or may not reflect my own**

-Raf

*

When I was in college, I worked as a peer health advisor with a bunch of my friends. We were known on campus as Student Wellness Advisors or SWAs. We made sure there were free condoms available in the dorms, hosted events to talk about health as a college student, and answered anonymous “Ask a SWA” questions from the earnest, “How can I make sure I never get herpes?” to the silly, “Am I going to get sick because toilet paper always sticks to my butt?”

It was in my capacity as a SWA that I attended a presentation one cool spring day given by our college’s Gender and Sexuality Center. I was excited, because the presentation was going to be about me! That is to say, about intersex people and how intersex fit into the LGBTQ+ label-potpourri. I hadn’t spent much time thinking about “intersex” as a term. I thought of myself more as a girl who’d needed hormones to go through puberty than anything else.

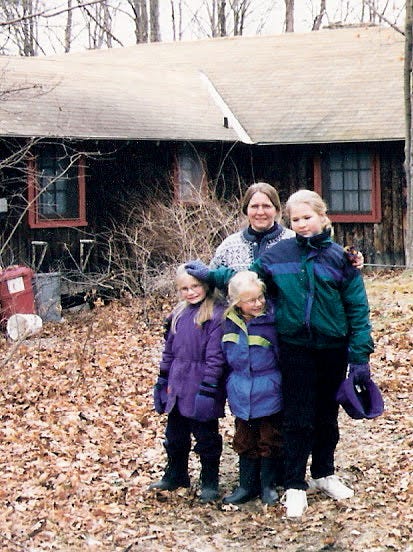

I have Turner Syndrome, which is a constellation of symptoms that arise from having a single X chromosome rather than the XX or XY pair that most of us are born with. I wasn’t diagnosed until the age of thirteen when my mom wisely observed that I was not following the same trajectory into puberty as my sisters. Estrogen and progesterone tablets have been my primary treatment ever since. Throughout high school, the goal in taking these pills was achieving puberty. To me, maturing into adulthood meant affirming my gender identity: I didn’t think of these concepts as distinct.

The gender piece was easy. I felt like a girl and had always been treated as one. But I would never be able to move forward successfully in my life without physically developing into an adult. I wanted to become a woman. My mother eschewed a lot of traditionally feminine pursuits. She minimized the presence of Barbies in our house and told me I “didn’t look like myself” in makeup. She didn’t want her daughters to be bound by the boxes in which society sought to confine women. The feminism she instilled in me tangibly helped me dream of more for myself. I was able to hold my own and speak up for myself when I was one of two girls in an advanced physics class in high school. After my diagnosis with Turner’s, I felt empowered to push back and embrace wearing floral, brightly colored skirts. Since I wasn’t athletic anyway, it felt natural for me to focus on performing arts and baking in my free time. As I thought more and more about what it means to be a woman in the world, it was hard to imagine dating or going to college, let alone launching a career or family, without starting puberty. My brain was ready, but my body needed some assistance catching up.

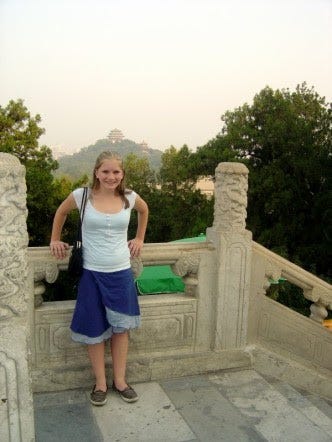

By college, I was happy, healthy, and taking comfort in the fact that my hormone replacement therapy was a widely available form of birth control. En route to the presentation at the Gender and Sexuality Center, I naïvely assumed that my input and lived experience would be welcome. After all, I am a walking, talking example of the fact that our bodies do not cleave cleanly into an XX/XY binary. Officially, I knew that this “intersex” term applied to anyone who wasn’t 100% biologically male or female. That includes anyone with a sex chromosome anomaly, which means me.

But as my friends and I took our seats and the lecture began, I felt a growing sense of unease. The presentation hinged on the following thesis: The biggest struggles facing intersex people arise from their parents and doctors doing surgeries on them as infants to correct ambiguous genitalia.

Of course this is a cruel practice that merits attention. It also isn’t the only intersex experience. I brought up the fact that hormone treatment had helped me affirm my gender, and had medical benefits for my long-term health. I was summarily dismissed. There didn’t really seem to be any meaningful space to discuss how sex chromosomes impact adult life and family formation. By the end of the presentation, I was left uncomfortable with intersex as a label to describe myself. I don’t have ambiguous genitalia, and gender-affirming hormones successfully allow me to present as a woman. I had been told that my medical care would allow me to live a long, full life. At 20, I was living out that promise.

Even then, I knew that sterility posed the biggest challenge to the full expression of my womanhood, a fact that I would need to navigate when I wanted to start a family. The medical reality is that being intersex makes reproduction and family formation more challenging. I already knew that my options would be either an egg donor or adoption. I wanted to know how other intersex people navigated that challenge. I was so baffled at being left out of this space that I applied to work with the GSC the following year. I didn’t yet have the perspective to articulate exactly why that presentation upset me so much, choosing to discuss in my application how I’d been disappointed in the lecturer's failure to discuss whole swaths of intersex experience. I came across as complaining, and didn’t get the job.

I wish we had talked about the diverse and full lives led by intersex adults. Because having only one X chromosome almost always delays or prevents puberty, the gender-affirming component of my care is inextricably linked to becoming an adult. I needed hormones to develop breasts and hips. I needed those same hormones for bone and muscle development. Forgoing hormones altogether was not an option: it would have been detrimental to my health. Moreover, as a young teen, I didn’t want to age into adulthood without the requisite physical traits. It was incredibly frustrating to have people constantly talk to me as if I were younger than I was. I wanted to be a woman, yes, but I wanted to be an adult just as much. Without the hormones that helped me through puberty, I would not have been able to establish the romantic partnership that I have now. It would have also impacted my career, as it’s nigh on impossible to move through the professional world reasoning like an adult yet looking like a child. Though my life might have still been incredibly meaningful, it might not have been marked by familial milestones of marriage and children.

I daydream sometimes about a Claire born in a different era, a young woman who never got to start hormones. I imagine that I’d lead a sort of solitary, monastic life. I might have taken an Emily Dickinson approach and devoted myself completely to writing. Or maybe I would have woven elaborate tapestries in a medieval European convent. I might have been a more interesting person, but much more lonely. Lacking an adult body, I can’t imagine I would have been allowed to participate in mainstream adult life. What happened to Mr. Rochester’s wife in Jane Eyre when her mental state left her incapable of fulfilling her societal role? She was locked in the attic. Literature is full of women who suffered dim fates as a result of their failure to successfully transition from maiden to mother. Maybe I would have ended up indentured or enslaved, bound to a life of menial work for others like one of the Marthas in A Handmaid’s Tale. There’s a Law and Order: SVU episode featuring a young woman who has Turner’s, in which her partner is depicted as a pedophile who has found a legal outlet for his deviancy. You can’t sexualize someone who has a child’s body, regardless of their chronological age. It’s weird.

The fact is that there’s never been a mental disjunct between who I am and who I’d like to be: I thought of myself as a girl, and then an adult woman. But both “girl” and “woman” are social roles in addition to physical ones. Hormone therapy has allowed me to enter the adult social world as a woman.

That presentation at my college was one of a litany of small instances that convinced me of the need to share my experience by joining the world of reproductive healthcare. Having Turner Syndrome makes me acutely aware of how hard patients work to advocate for themselves and understand their diagnoses and care. I feel deeply connected to the fight for reproductive freedom in our country, from IVF to gender-affirming care to abortion. I place IUDs in my work regularly, and when my patients ask me, “Have you gotten one of these?” I respond that I have my own health needs that make birth control pills work particularly well for me. I am also hyper-aware of legislative attacks on contraception because I am one of the many, many people who use it for medical conditions beyond pregnancy prevention. I’ve always understood attacks on reproductive freedoms to be a means of asserting control over other people’s bodies, including their roles in the conception and creation of future generations. There is no other logical reason that anyone besides my family and my doctor would care what medication I take or why.

I take joy in the feminine body that my hormones gave me. I work hard to take care of that body, and treat it with love and respect. That does not change the fact that it will never do what so many female bodies do: it will never become pregnant or give birth. I will never experience the physical ups and downs of a pregnancy and postpartum journey.

Sometimes, I make myself a little pro and con list about not being able to carry and birth my child:

Pro: I will not be advised to avoid soft cheese for 40 weeks.

Pro: I won’t have to physically recover from childbirth while caring for a newborn.

Con: I won’t get to feel my kid move inside me.

Con: Neighbors will inevitably see me with a newborn and exclaim, “I didn’t even know you were pregnant!”

My partner and I have recently started pursuing parenthood. It’s been a bit of a reckoning, because it has exposed my chronic medical condition. There is no way to hide from those in my social circle that I will not be carrying my own child. It has also got me thinking more about that pesky little term, “intersex.” I still don’t know if “between sexes” is the right way to describe the multitude of bodies that term encompasses. It’s not a linear X-Y- axis, not a Cartesian graph. One can certainly have normal sex chromosomes and ambiguous genitalia. By contrast, most of us with chromosomal anomalies do not. Our sex is determined to be either male or female at birth. If our physical bodies do not always tick the morphological boxes required of them to be conclusively deemed one sex or the other, why on earth should our social expression of gender or sexual orientation? Our brains and bodies don’t exist in perfect alignment. I love how nuanced and diverse human bodies are. I spend a lot of time talking to people about the incredible range of female reproductive experiences that are all still considered normal. In that spirit, it is only appropriate that there is a word for the fact that people cannot be dumped into one of two biological buckets.

I am proud of the ways that my experience connects me to the LGBTQIA+ community. I have joked to people that having a baby through surrogacy and egg donation is the gayest thing I’ll ever do. As grateful as I am for my adult female body, gender-affirming hormones could not give me a second X chromosome, nor could they restore my fertility. For most of my life, this will be irrelevant. At this moment, though, I’m grateful for the empathy and connection with same-sex couples that I’ve gained through my experience with Turner’s.

Becoming a parent is an act of optimism. I hope that my children will have a better life than my own. I want them to thrive, which means that I want them to grow into well-rounded adults who positively impact the world they live in, regardless of whether they dress or behave in deference to specific gender norms. Turner Syndrome gives me a unique stake in the reproductive health care space. It’s a shame that its rarity causes it to be left out of conversations about gender and sex, because it has given me an incredibly rich experience. And I’m not afraid to talk about it.

Claire is a midwife and reproductive health clinician who lives and works in the Bay Area of California. She has a decade of experience caring for underserved populations. She enjoys musicals, knitting, and taking long walks with her sweet dog Bridget. She is incredibly grateful for her supportive partner, Matt, as well as her parents and sisters.

Mine certainly will! Eugenics bad!