Welcome to 2025, subscriber! It’s good to be here with you.

And let me say, without theatrics (okay, with a few theatrics), that I’m finding it especially good to be here, as in: alive, well, uncommonly excited to move through spacetime doing things I love to do, like writing, and reading others’ writing, and eating buttered croissants. Was there ever a question that you wouldn’t be doing these things? asks the new subscriber. To which I can only offer these hyperlinks in response.

Yes, 2024 was a helluva year – one that I’m more than glad to have behind me. Though, let’s be real: writers don’t necessarily leave things behind us, do we? The hot mental trash that might metastasize into one person’s migraine or chronic toothache may very well become the substrate for another’s essay collection or stage play. I’ve got to count myself lucky here, as the same tendency toward creative transmutation that got me into 2024’s predicament is going to be precisely the thing that gets me out of it in 2025! Ah, the enchanting cosmic ouroboros of the writing life!

And to that end, subscriber, I’d like to share another little essay on conning, a topic which is swiftly becoming one of my favorites. I had the good fortune to make the book fair rounds last fall, and when certain patrons learned about the plot of my novel, there inevitably followed a mutual nerding-out about grifting in the U.S., from famous solo acts to MLMs to forms of the prosperity gospel both likely and unlikely. I’ve nicknamed these lovely patrons Grift Geeks, and always feel, as I’m sure you can imagine, an instant camaraderie with them. Regardless of our personal experience with the Art of the Con (or merciful lack thereof), we’ve got an intense shared interest, not to mention primary texts for days.

This one’s for you, Grift Geeks! Here’s to staying safe, savvy and un-conned in 2025.

*

In those first few weeks after the exposure of the grift that had very nearly ruined my life – when I broke from my “best bro” and his associates only to discover the depravity of his intentions and those of the organization he’d been working for, when I came close to losing my sanity as my wife and some close friends created a mini war room to research my antagonists and salvage what of my money and compromised accounts could be salvaged – I often wondered how he'd done it. I thought about this as I attempted to navigate life in the small town upon which Best Bro’s spiritual leader held considerable social and economic purchase, as I limped PTSD-stricken through the motions of the job Best Bro had done his very best to take from me, along with my engagement and a whole host of other things. One minute, you’re a young professor who’s made a very cool new trans friend in the college town where you teach creative writing. And then you blink, and that very cool trans friend has nearly succeeded in destroying your life.

How did he do it?

“Is there, like, a PDF on the dark web called How To Destroy the Codependent’s Sanity?” I wondered aloud to my wife, who by then had heard me ask some version of this question hundreds of times. “Are there trade secrets?”

And while I don’t pretend to know how tricks of the trade are communicated in the criminal underworld[1], it was with the benefit of increasing distance, research and self-knowledge that I began to realize that, no, Best Bro had not executed some arcane act of personality-modifying wizardry. All he’d done was correctly identify my weak points and work them using various techniques of thought and behavioral control. This form of authoritarianism is precisely how cults maintain their vise-like grip on adherents; Best Bro’s long con had merely been to run a cult with me as his single, enthusiastic devotee. By the end, I thought this rando millennial in a thrift store duster and cowboy boots was a bodhisattva who’d done us all the immense favor of briefly touching down on Earth.

Happily, there are few crises that can’t be solved through research. So I researched, and I found that this one-on-one life-ruining grift in which the con artist poses as a guru-like or salvific or even romantic figure to the mark is not terribly uncommon in the world of the mega-celebrity, but what I didn’t suspect is that it can happen to anyone. If anything, conning is a democratic art: it doesn’t matter if what’s on offer is your multi-billion dollar lifestyle empire or just your “willingness” to perform hours upon hours of uncompensated labor. If the grifter wants it, he’ll find a way to extract it from you, and do it with a smile.

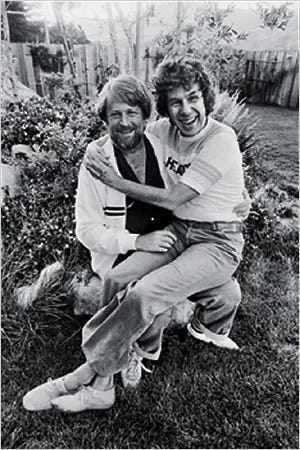

Poring over the annals of this particular style of long con – which I’ve nicknamed Failure to Thrive – I found two examples that struck me as being similar to my own grifting in method and execution: the cases of Ira Herschkopf and Marty Markowitz, and Eugene Landy and head Beach Boy Brian Wilson. I came upon the Herschkopf-Markowitz story by way of a gripping podcast called The Shrink Next Door – later adapted into an AppleTV show of the same name starring Paul Rudd and Will Ferrell – and learned of Brian Wilson’s relationship with Landy from the film Love and Mercy, in which Paul Dano and John Cusack play Wilson and Paul Giamatti plays Landy.

Both Markowitz and Wilson were well-resourced marks: Markowitz had access to his well-to-do family’s textile business as well as a large trust, and Wilson’s lyrical and harmonic genius had catapulted the Beach Boys to fame. Both met their grifter-gurus at low points: Markowitz’s sister wanted him to seek Herschkopf’s help for his paralyzing anxiety attacks and fear of commitment, and Wilson’s wife had sought Landy’s help for Wilson’s tendency to lie in bed in a dark room bingeing drugs all day. (Notably, both Herschkopf and Landy were practicing psychiatrists, and both were stripped of their licenses as a direct result of their “treatment” of Markowitz and Wilson.)

In both cases, what ensued were decades of horror. Herschkopf orchestrated Markowitz’s estrangement from his sister, moved into his home in the Hamptons and was living there with his wife while Markowitz lived in the guest house – the Bloomberg reporter who broke the story of Herschkopf’s abuse initially mistook Markowitz for the groundskeeper. Landy kept Brian Wilson on a strict diet and 24-hour supervision, frequently berated him, and dosed him with psychotropic drugs in dangerous amounts. Both “controversial” treatment plans resulted in the psychiatrists becoming business collaborators with their patients, as well as the sole inheritors of their patients’ fortunes.

It was through my research of these stories that Best Bro earned a new nickname: Cowboy Psychiatrist. Though thankfully much more short-lived than either of the relationships described above, ours was no less sinister, his level of involvement no less extreme. First, he was present in virtually every sphere of my life: domestic, professional, and everywhere in between. Then, once he’d become both my closest friend and creative writing student, he saw that I became his student of life: as it turned out, he knew many things that I didn’t, for his had been a difficult life full of difficult circumstances, one that a wealthy and advantaged person such as myself should work to rectify. And as I was helping to repair his life and build him a literary career, he would do me the immense favor of sharing his incredible wisdom with me – wisdom that I could live by. Once I had adopted this ad hoc treatment plan, all other ways of living seemed irrelevant, and anyone’s opinion to the contrary seemed woefully clueless, even suspicious. Oh, you think my cool new friend is really weird and perhaps creepily attached? You don’t like the way my eyes go glassy whenever he's in the room, or that funny habit I have of handing him all my credit cards? Have you noticed how my life has literally never been better, or do you just not care about me as much as he does?

But Raf! I hear you asking. How could you possibly have thought your life had “never been better” when it was actively falling apart? And how could Markowtiz or Wilson have thought anything similar? It’s a great question, subscriber, and one I’m going to set about answering right now. Here is a short and (mostly) complete list of what makes one an ideal mark for a Failure to Thrive con.

1. Fear

Ah, fear! The great destroyer of inner worlds. The title of the first chapter of Brian Wilson’s memoir, the thing that had Markowitz hyperventilating on the floor of his father’s factory, and my erstwhile ghost of Christmases past, present and future.

It’s only human to experience fear, and certain amounts of fear function as useful signposts: we might not be that well-advised, after all, to attempt a jump across this rocky chasm, or to proceed toward the bulky figure rushing at us in this dark alleyway – best in both cases to listen to that amygdala-burst of fear and turn around.

But what of the fear that’s not a warning sign, but a way of life? What of the nattering internal monologue that’s so insistent upon the horribleness of the world? So bound to obtain complete and utter certainty[2] about the neutralization of any and all perceived threats that anything less is cause for panic and misery? This is not a prehistoric fight-or-flight response “dialed way up,” as pop psychologists weirdly keen on justifying the (omni)presence of anxiety in our lives seem to want us to believe: this is the human ego curdled into a position of hyper-negativity and kept there by the limiting beliefs doled out to us day after day. I describe these beliefs as “limiting” because they circumscribe our lives based on senses of lack, futility, and urgency – conveniently, the selfsame concepts also employed in selling things to people, from self-optimizing lifestyle apps to Ozempic to Brazilian butt lifts.

Is it true that I am a worthless human being because I’ve gained fifty pounds? Definitely. Is it true that the world as we know it will end in a fiery blast on X date because of Y historical event? Certainly. Is it true that, right this instant, I am developing a tumor that will somehow kill me and everyone I love? Without question. Fears like these are pernicious: exaggerated though they are, they appear to have enough of a basis in reality to seem tenable, though not enough to be conclusively disproven outside of, well…not coming true. And even when they don’t come true, there’s little time for celebration before a new bumper crop of fears emerges to dominate one’s mind. Living like this – lurching from panic to panic – is utterly miserable and exhausting. Because it’s an attitude born out of pessimism masquerading as “realism” and a resistance to both uncertainty and impermanence (both facts of life), there is no Ultimate Resolution of a Single Fear that can disprove this mentality. Meaning: without meaningfully rejecting the premise that the world is fundamentally bad and full of threats, there’s no end in sight for the fear-afflicted.

2. Self-loathing

I’ve said it once and I’ll say it a million times more: self-love is the greatest defense against any form of authoritarianism. And I’m of course not talking about the sort of narcissistic self-regard that gets one interested in enacting behavioral coercion and control in the first place. I’m talking about simple faith in oneself. Knowledge of your own goodness, for which is frequently required a coextensive belief in the goodness of others.

I can read your mind, subscriber! (Though not in a creepy codependent way, I promise.) You’re telling me how to avoid getting conned, yet you’re asking me to believe in the goodness of others? Wouldn’t holding such a belief make me a total naïf, and therefore more likely to get conned in the first place?

It’s a fantastic question, and I promise I’ll answer it later on in this essay. But in order to get there, I’ve got to explain how self-loathing and fear are related. We know that in order to live a fear-based life, you’ve got to hold the belief that the world is fundamentally bad, and that its constituents are for the most part harm-intending and bad as well. Naturally, this would mean that you, very much a part of that world, are quite bad, too. In fact, it’s often the case that holding this worldview imbues one with a sense of Original Badness. Though various politicians and landlords and irritating bosses may function as shallow vessels of badness, it happens to be a single, fearful person who is actually the source of all things awful – the unmoved mover of malignance, if you will.

I can’t speak for Markowitz or Wilson – though I will say Markowitz’s imposter syndrome and Wilson’s coke-bingeing kind of speak for themselves – but I can say that my own self-loathing was fairly transparent. The facts of my life were wonderful: published books, a salaried job with a title that conferred respect, an incredible partner, a three-bedroom home. And yet! I still felt that I was quite shitty, that I had fallen short of the universe’s exacting yardstick. There was, of course, the failure of any of those books to “break out” into bestseller territory. And then there were the numerous ways I seemed to be falling short at work. And then there was the fact that I was a middle class piece of garbage who couldn’t even manage to use my considerable privilege to relieve the financial problems of everyone I met. Could it even be said I’d amounted to something if that “something” was never enough? And what did it matter that many would find my life circumstances enviable if I was too busy envying others’ to enjoy them?

I suspected that I might be worthless human refuse – I just needed something (or someone) to conclusively confirm it for me. Which brings me to #3.

3. Willingness to give it all up to (a) “god”

Researchers have often described the anxious and depressive brain as prone to “psychological inflexibility,” a mental state marked by rumination, a sense of futility, a lack of adaptability in terms of personality and little imaginative elasticity/capacity for entertaining hypotheticals. In other words, the fearful, depressed and inflexible brain is inclined to hold two short-sighted beliefs: 1) that everything is very bad; 2) that things are highly likely to either stay as they are or change for the worse.

It's hard to get anything done when subsisting in a state of psychological inflexibility, and it’s easy to believe that the things you have gotten done are either fake or about to be snatched away from you. You may get to a point where your fear and self-loathing feel unmanageable – indeed, they’ve come to dominate your life, and the good things remaining in it seem ready to scatter. This is the point at which you (or your sister or your wife) rings an expert for help. You’ve hit rock bottom, so you seek guidance. And maybe even salvation.

Okay, sure, you’re thinking. But when the grifter shows up in his weird boots and unseasonably wide-brimmed hat and starts recklessly negging you, why don’t you immediately catch on? Yet another great question, subscriber! And here I’ll refer back to the bit about the goodness of others in the Self-Loathing section.

Can you imagine that you’ve tunneled so deep into ideas of your own loathsomeness and separateness and smallness, become so miserly with love for yourself that it’s caused you to be miserly with love for others? Imagine that this miserliness comes out in the form of paranoia, often about the ones who love you the most. “I’m nowhere near good enough for her, so she must not be good enough for me, either,” you think, bizarrely. Or “My warped, shitty little brain has felt X petty emotion about Y kind person, so I can only assume they’re secretly unkind and thinking the same about me.” On and on you go, judging others by way of judging yourself, pushing people away through self-recrimination that you don’t recognize as such, and then pointing to the ensuing distance as justification for your continued self-loathing. “Look!” you say, almost pleased with yourself in a twisted way. “I really am a heinous trash heap! I was right all along, suckers!”

It's not hard to imagine how such a cycle of insanity would make one have several panic attacks a day, or want to rail fat lines of cocaine: both were certainly true of me. It’s also not hard to imagine how said cycle would lead you to disbelieve in the fact that the world and its denizens are not all bad, that in fact there are probably quite a few of them who earnestly love and care about you, who would delight in seeing you flourish. You dig in your heels, believe that any claims to another person’s goodness or selflessness or desire to do the right thing are broadly Pollyanna-ish, fairytale beliefs held by innocents who haven’t suffered as you have.

Perfect! You’re now ready to be grifted out of house and home!

Hey, you! Does your life feel unmanageable? Are you a fucking mess, and a loser to boot? Stop crying, and tell me if you’re willing to accept that you do not – and never could[3] — have the answers, and that they can only be found outside of you? Are you willing to accept that change is impossible, unless undertaken at the hands of an expert who just so happens to have every last one of those elusive answers? He’s studied your case closely, even read some primary source materials about your pathologies. He does indeed have the power to make your life better, and he will deign to do it for the generously low, low price of everything you own and everyone you love.

Still not convinced? You do realize you could die, don’t you?

So there you have it, subscriber: my first stab at an anatomy of Failure to Thrive. Contrary to what Best Bro would have you think, the only “art” of conning is a supremely crude one: the grifter simply turns up the volume on that nattering, negative voice in the mark’s head. Once the mark is distracted by the noise, the grifter can work on stealing everything that isn’t nailed down.

The good news is that one can become grift-proof by getting better acquainted with self-love, intuition, and the true – and important! – ideas that change is possible, and we are each of us the ultimate authorities on what we need to flourish in this life. Namely, we are already in possession of the answers to all of our questions, and living is simply the process of “learning” what we already know. Whether that living-learning takes place through reading, or loving conversations with family and friends, or making art, or going on long walks or having far-flung adventures, it is most certainly an incremental undertaking, and sometimes even a hard one, but never so needlessly hard as giving it all up to a faux god who believes all your problems can be solved by cutting him bigger and bigger checks.

I foresee 2025 being a year of self-love, community and trust for me. I hope it is for you as well, subscriber.

[1] My apologies – I believe the less problematic term would be the “grifting and extorting community.”

[2] Spoiler alert: this is impossible. My apologies if you’re anxious, an empiricist, or – as is so often the case – both.

[3] I mean, no offense but…come on. Look at you!