One of the more crazy-making things about being an American, reader, is the fact that we know enough about life in this country to be perpetually on the lookout for The Scam, yet we rarely know enough to actually find it.

Back in the 90s, I remember how hackle-raising it was for neighbors to open the door to me, a ten-year-old Girl Scout, selling magazine subscriptions. What kind of smooth operation was I running with these $3 issues of Highlights and Tiger Beat and Zoobooks? Who’d put me up to this? It was my troop leader, I said, and produced the laminated sheet of paper indicating how many more subscriptions I’d need to sell in order to get the beach towel, and then how many beyond that for the plush dog, a Top Seller Item that I wanted very badly. This display of evidence left most of my neighbors unmoved, and so did a pivot to pathos: if I rhapsodized about how great I knew owning the plush dog would be, how Ally had gotten one just last week and brought it to school and it was all any of us could talk about, the door-answering adult would sigh and make some halfhearted excuse about needing to start dinner despite it being a little after 3:30. One wonders how that adult might have received me had my backpack contained not a stack of magazines with Jonathan Taylor Thomas’s face on them, but an elixir scientifically proven to help them drop fifty pounds, be happier in their marriage, and restore the meaning long missing from their lives? If I was not a young girl who wanted a stuffed animal but a clean-cut Tony Robbins type who seemed to have all the answers, and was miraculously willing to share them?

If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is, I repeated like a mantra throughout my twenties, eschewing offers of friendship and romance from individuals who seemed to genuinely care about and want the best for me – an impossibility, I was sure – in order to choose, time and again, the company of confidantes and lovers who seemed shinier and more compelling by virtue of their indifference. I once practically bullied someone into a friendship-like situation because I was so enchanted by their knowledge of the Frankfurt School (and quite insecure about my own); later, they ended up guilting me into footing a few thousand dollars’-worth of personal bills for reasons that seemed to make sense at the time but feel less and less coherent the farther out I get. Not a year later, I listened as a weebish young man dressed me down while I wept on the IKEA comforter he’d strewn with waxy rose petals in anticipation of sex I was in no place to have: You’re so lucky I’m with you, because I don’t know of any other guys who’d put up with crazy shit like this.

All my young life, there was something that made me despise and suspect genuine open-heartedness, to insist on its nonexistence. It couldn’t be that these kind-seeming art nerds really wanted to be friends with me, that the editor of this literary magazine was really taking an interest in what I had to say, that these students really thought of me as a capable teacher. Surely, these positive sentiments were deceptions, and not to be taken at face value. And yet, were some confidence viper to slither up out of the grass and push my buttons in just the right way, I would not hesitate to proclaim that I’d found it at last: the thing too good to be true, and yet true nevertheless!

And slither he did, an experience I’ve begun to write about, and which you can read more about here and here. Much has been said in books and film about the abuse of The Scam – enough horror stories to account for several skeletons’-worth in the dark closet of the American mind – but little has been said about how that abuse can be transmuted. It’s typically assumed that us poor unfortunate naïve victims crawl back into our sad little hidey-holes to spend the rest of our lives trembling at whatever shades chance to darken our doorways. Surely it couldn’t be the case that one could meet with the ultimate shame of falling for the con and not only emerge, but emerge wiser?

Americans are a people obsessed with material reality and the surfeit or scarcity of the objects around us. The con artist understands this fact very well, and is happy to use it to his advantage. His canny ability to show up at precisely the right time, in possession of exactly the thing you lack is more often described as uncanny, but such is the nature of The Scam. The big grift – the one intent on activating our mutually-dependent senses of pride and shame in order to take us for everything we have – looks different than a simple pickpocketing or sale of a counterfeit handbag. It looks like disarming geniality, like true empathy and compassion – the kind of “friend” who knows you so well and so instantly that you’ve scarcely invited him into your living room before he’s begun dwelling in your gut like a tapeworm, keen on overtaking your entire system.

The problem is that this “friend” is a brilliant mimic of a kind-caring-generous person, or at least he would be to the untrained eye. You may have observed that ours is a culture rife with self-loathing and isolation. We have been living under a model of problem-solving consumption that informs us time and again how very bad various aspects of our lives and bodies are, and how those very bad things – whether they be 50 extra pounds or an inability to keep the car clean or the too-small size of one’s house – can be fixed via a series of hassle-free payments to someone(s) who have all the answers. And as we receive this whiplash-inducing set of messages, we are most often parked in front of a screen or else holding one in the palm of our hand, peering not at another human face but at its digital facsimile in a little glowing terminal. We are wrong and alone and striving all the time to be less wrong and alone – and then along comes someone with the magical ability to make everything right.

But here’s the thing, reader: to the trained eye (i.e. the eye of long con survivor), there is a huge difference between the actual kind-caring-generous person and their mimic. For the kind-caring-generous person does not purport to know you, to just happen to have the answers to your most pressing set of problems, to want to share these hard-won secrets with you out of a sense of superhuman beneficence. The actual kind-caring-generous person admits to knowing only a portion of you and wanting to get to know you better on your terms. The actual kind-caring-generous person claims no answers to your life’s most pressing questions beyond, say, the question of whether they’d like to grab a coffee or go for a walk or see a movie. (The answer is most often yes.) Most importantly, the actual kind-caring-generous person is interested not in keeping obsessive tabs on the objects in your possession or theirs, is concerned not with extraction of energy or personal enrichment but with an ongoing exchange – of objects, maybe, but chiefly of the ideas and feelings and shared experiences that went into the creation of those objects, that continue to imbue them with significance.

But we Americans have been so mercilessly trained in the joyless pursuit of personal enrichment that we’ve lost all sight of the concept of mutual enrichment, so much that many of us regard it as totally alien. At least it felt that way to me for years, and it primed me for an insane experience in which I felt I was benefiting so immensely from a scam of a “friendship” that it seemed the very least I could do was hand over my every resource to my new “friend.” What appeared to be an instance of mutual enrichment was actually a hellaciously transactional experience, a high-stakes spiritual quid pro quo.

Happily, I’ve found that one of my favorite ways to transmute the pain of this experience is through actual generosity. It was my obsession with what I supposedly lacked that landed me in such a place of need. I lacked a sense of my inherent worth and the knowledge that there was more to my life than dollars earned and followers gained; I felt I “needed” no-strings-attached external validation, and someone showed up offering just that. But nowadays, I’m far more interested in what I have, and how it could be used to elevate and enrich others along with myself. To be clear, I’m not keen on giving things away with the ultimate goal of living an ascetic life. Rather, I’m interested in kind-caring-generous mutual enrichment. This, and not fear, shame and resource-hoarding, has been what’s gotten me out of the unspeakable hole of my PTSD. It’s the foundation of my marriage and my longest-lasting friendships. It’s what’s kept me close to my loving parents through periods of confusion and self-estrangement. And it’s pretty much the only way I want to be in the world.

Sounds like a pretty happy ending, huh, reader? The only problem is that little item I mentioned about 1,500 words ago – the fact that everyone’s always on the lookout for The Scam but incapable of actually finding it. After years of living in suspicion of the open-hearted, I forgot that I’d become an object of suspicion when my heart finally creaked open.

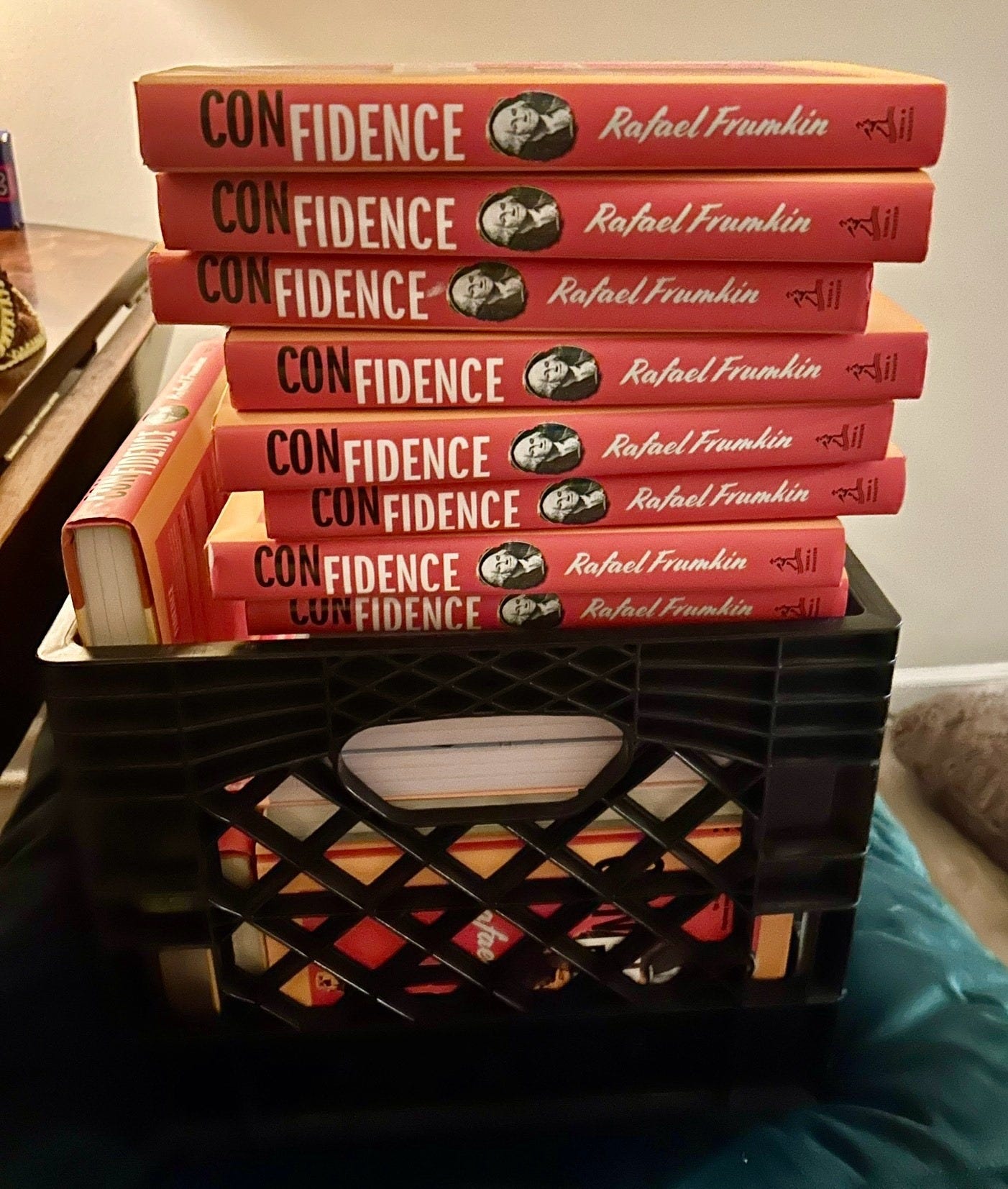

Case in point: I have a whole bunch of hardcovers of Confidence lying around the apartment my wife and I are currently renting. Like, way too many, and accumulated for the reasons one might accumulate hardcovers of your own book in 2024: events cancelled due to COVID outbreaks; events poorly attended due to fear of COVID outbreaks; books underselling at a given event because of raw luck1 or the fact that the book can be gotten much cheaper online, etc. etc. Surveying the stacks upon stacks, I thought it might be nice to try to book some new events and bring these books along, and so wrote to a few education-oriented nonprofits – universities, public libraries and the like – where I had personal connections. My offer: I’d love to do an event and waive any speaking fee, instead diverting a portion towards the heavily discounted purchase of some hardcovers to be given out to attendees of the event as gifts to take home and read. It seemed like a fun idea, and a great opportunity for mutual enrichment: I’d get rid of some hardcovers while making a few book sales for my publisher2, and the institution could book an event with me for a fraction of the price, plus have signed and inscribed gifts to give to the attendees.

This offer didn’t go over as I’d suspected. The first time it was rejected, it hurt my feelings. The second time, I began to wonder what I was missing, if there was some rule I’d mistakenly broken3. And the third time, in conversation with a very smart Book Professional who understood where I was coming from but whose superiors didn’t, the realization hit me square in the forehead.

“It’s just – people are so used to being scammed, they don’t really understand an offer that seems too generous,” she said, and I was immediately transported back to my neighbors’ front steps in 1999. All I’d wanted then was for someone to buy three more $3 magazines so I could have a plush puppy. And what I wanted now was to arrange highly affordable events that would benefit university students and library patrons while introducing new readers to my work. In both cases, I was showing up open-heartedly, unguardedly. In both cases, I was not being received as I’d wanted to be.

To be perceived as a scammer as a result of lessons learned after having been aggressively scammed is a layer cake of irony that I’d prefer never to eat, but here I am eating it – though it’s less cake than a slice of humble pie, or else some other pastry intent on reminding me of my unerring humanity. It feels strange to have clawed my way out of the world of lack-obsession and need-conviction as a means of self-preservation only to realize that I am now regarded as the shifty-eyed person of interest. What a time to be alive, when the scam victim is mistaken for the scammer, and the actual scammer continues to be hailed as untouchable.

If you’re wondering what’s to be done, reader, I must admit that I don’t have an answer. If I could invite everyone for a 335 million-person fireside chat during which we could all take turns processing our various grift-traumas, I would. But alas, I’m just one person, and a novelist no less, so I’ve got to content myself with writing little essays and hoping that someone reads one of them and thinks to herself, “Oh yeah, I totally vibe with that,” and then sends the link to a friend, who reads it and feels a hair – or, dare I say, a whole fraction(!) – better than she did before reading it? It may not be our entire ethically imperiled country doing life-changing shadow work before a warmly crackling fireplace, but at least it’s something.

Oh, and if you would like a vastly discounted hardcover (or a whole stack of them) and a lively talk about writing The Scam only to get scammed, you know where to find me ;)

And in one truly insane local case, the Svengali-moves of the con artist and his affiliates. But that’s another story for another time.

Which the publisher takes note of, and which would make them that much likelier to have me back for another book, even if this one isn’t a runaway bestseller (or even a royalty-earner).

Book people reading this: please let me know if I’m missing something here! I have almost passed the point of mortification and crossed over into the realm of genuine curiosity.

Aww, damn, I don't know anything about events but that's one of my very favorite books and I'd definitely drag some friends to a 'Confidence' party so I hope you have some luck!!